Advocating Human Dignity and Political Accountability in Mexico

On 6 March Camilo Pérez-Bustillo, a leading scholar on human rights in Mexico, came to the Resource Centre’s breakfast forum to offer his insight into the deadly drug war between the state and the cartels.

Hovedinnhold

Ever since Mexico’s former president Felipe Calderón initiated a massive military offensive against the drug cartels in 2006, the price in terms of human lives has been heavy. In January 2012 the authorities released a report according to which almost 50,000 people had died in the drug war since 2006, but as the New York Times reported, a lack of transparency and of a reliable system for registering deaths at local levels led many to challenge the figures.

Interior secretary Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong Human recently stated that the death toll was 70,000, while human rights scholar Camilo Pérez-Bustillo supports independent activist groups’ estimate that the number of deaths is currently over 100,000.

A critical voice

Pérez-Bustillo is Research Professor of the Graduate Programme in Human Rights and the Faculty of Law, Autonomous University of Mexico City (UACM). He has written extensively on global human rights discourse and practices and their historical, philosophical, and ethical origins. He is also an expert on the rights of indigenous peoples, and migrants, refugees, and the displaced ("peoples in movement") in the context of poverty and inequality.

He frequently appears on Al Jazeera English as an expert commentator on Mexican politics and on the country’s problem of violence and human rights abuses. His latest appearance was on 15 February, when he gave a critical analysis of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s plans to curb Mexico’s cycle of violence. The segment can be viewed here.

Visiting researcher in Bergen

Since 1997 Professor Pérez-Bustillo has worked with the Bergen-based Comparative Research Programme on Poverty (CROP), on questions of human rights and poverty. He recently arrived Bergen as a visiting scholar at CROP and UiB Global. During his stay he will collaborate with colleagues and work on a book project.

He appeared at a breakfast forum at the Bergen Centre for International Development on 6 March, where he discussed the ongoing and deadly drug war in Mexico, together with Benedicte Bull from the Centre for Development and Environment.

Close alignment with the USA

Pérez-Bustillo sat down with UiB Global ahead of the breakfast forum, to discuss Mexico’s drug war and the larger issue of democracy and human rights in the country. In his view the Mexican political system has not seen the same leftward turn as other Latin America because of a geographical and historical closeness to the USA:

– We can look at the map of Latin America, and look at the geographical and economic proximity between the two countries. Mexico is in the US aligned camp, which is manifested in the UN, where the country takes the US line. It’s very different from the foreign policy of Brazil, a country with a different grasp of their political autonomy.

“The victims become criminalized”

According to Pérez-Bustillo this alignment forms the basis of the Mexican drug war and of illegal trafficking of migrants, two intertwined phenomena which are fuelled by free trade:

– The drug war and migration policy can be seen as case studies of a broader phenomenon. In both cases what happens is the result of US government’s political priorities. It’s a question of supply and demand, in strictly economic terms. Free trade produces movement. The EU is also an example of this, with Schengen and migration from the outside. In the North American Free Trade Agreement, migration policy is not factored in, but you have free trade as an incentive for migration, for illegal trafficking, and Mexico has become the corridor. The victims become criminalized. There is an incentive for people to move at a high cost, producing high profits for traffickers. It’s the same with drugs, and the two become intertwined, involving the same actors. In the free market logic, the only answer is the legalization of both migration and drugs. The suffering is the result of policies imposed by the US, says Pérez-Bustillo, who claims the problem is compounded by systematic corruption and abuses of power within the Mexican government:

– Government officials in Mexico have become complicit in the trafficking, and are sometimes directly involved. Hundreds of immigration police officers have been dismissed because of corruption, but nothing changes in the structural conditions. The structure of the state is permeated by crime. The state itself is engaged in criminality, including human rights crimes. And because the conflict is defined by the government itself as a war, they should be judged according to the standards of the Geneva Conventions. Mexican activists have filed a complaint against Calderón over war crimes. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty, even the US Government have documented human rights violations, but this has no consequence for US policy, says Pérez-Bustillo.

A need for popular movements

– How do you see change coming about? Can it realistically come through leadership by members of the political elite, or rather through grass roots movements?

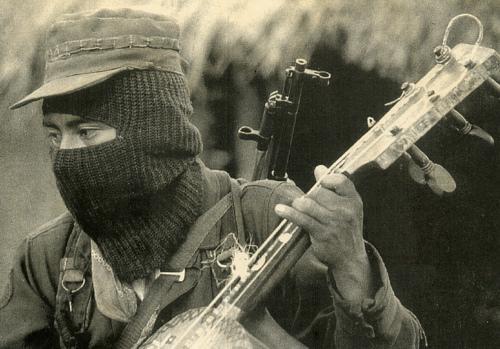

– Changes need to come from below, and we have seen it in the form of the indigenous Zapatista movement in the southern state of Chiapas. The processes are similar to Brazil, Argentina, Colombia and Chile. In Brazil there have been land reform grassroots movements. In Argentina it’s the unemployed. In Chile it’s the indigenous and the students. In Colombia it’s the indigenous and people of African descent. In Mexico such movements are situated in the poorest regions, among the indigenous. Internationally there is an expectation that change comes from the top, such as in Venezuela, Ecuador and Cuba. In Mexico it’s more difficult for movements to be visible, because of the government’s alliance with the US. In the states of Guerrero and Chiapas there are military interventions against communities. In Chiapas this has been the case since 1994, after the armed Zapatista rebellion. What we now see in Guerrero is the emergence of peasant movements among indigenous people, to create community based police forces, to protect them against drug traffickers and mining and forestry companies, which exploit and exhaust resources. The big companies have international support from among others the World Bank, as well as military support. What we’re seeing is really accumulation by dispossession, says Pérez-Bustillo.

No call to arms

However, the human rights scholar warns against armed rebellion:

– Given Mexico’s geopolitical situation, armed rebellion is very difficult as a successful path. It worked in Nicaragua and Cuba, but failed everywhere else. For the Zapatistas it worked to put the issues on the agenda, through peaceful forms of resistance, but also through self-defense, an assertion of self-determination, to say ‘we will govern ourselves’, an expression of democracy and dignity, an assertion that ‘we will not depend on the government for protection, since the government is an aggressor’. This way the people are becoming ungovernable, demanding a re-foundation of the Mexican state, with a new constitution. The hope is a transition from representative to participatory democracy, to a recognition of indigenous rights, to a state which defines itself as multicultural, says Pérez-Bustillo, who bears no illusions regarding the challenges to achieving such changes:

– There is a big problem of ideology and consciousness. The North American Free Trade Agreement was sold to the Mexican population with a promise of a transition from third world to first world country. Those messages are still very powerful, and the media play a huge role. We need to democratize media, to fight for indigenous radio, for example, and to inspire broad movements such as Occupy Wall Street in the US, the Arab Spring and the Indignados movement in Spain.

The Zapatista movement has made use of modern media to make its voice heard, also at an international level. This has led to relations with similar movements in other countries, such as the Shack Dwellers Movement in South Africa, who have made a Youtube video in support of the Zapatistas.

Opportunity in crisis

Paradoxically, Pérez-Bustillo sees an opportunity in the global recession, which has also hit Mexico:

– We saw sparks of indignation in Mexico last year, as a result of the global crisis. This crisis could spark changes in the right direction. Mexico is so incorporated in the US economic system that the elite is more exposed to that country’s problems. We could play to that weakness with respect to popular movements, says Pérez-Bustillo, who also sees the potential of a transnational movement involving some of the 30 million people who have migrated from Mexico to the USA.

“The bottom line is impunity”

The scholar has likened the situation in Mexico to the one in Syria, but does not advocate international intervention:

– I’m not looking for international intervention to determine the future of Mexico, which would compromise self-determination. The US considers Mexico as its back yard, but we want them to be held to account for the consequences of their actions. We’re calling for intervention of a different kind than what we saw for example in Libya. What we’re talking about is international human rights standards being respected, and that international companies should not be permitted to exploit resources in breach of international standards. The UN hasn’t taken up the problem, because what happens in Mexico is regarded as a US issue. The US talks of human rights violations in Syria, but does not talk of it in Mexico. Yet the death toll is similar. The US is not held to account, but holds Syria to account. There has to be a uniformed standard. The bottom line is impunity, and Mexican leaders should be held to account for their actions. However, all of the concerns I have highlighted in this interview are now heightened by the return to power of Mexico’s former ruling party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party or PRI, through current President Enrique Peña Nieto, which ruled Mexico as a one party state from 1929 to 2000. The PRI’s historic responsibility for authoritarian repression during this period was never accounted for, and there is no reason to have confidence in its respect for human rights in the context of the current crisis, says Pérez-Bustillo.

This article includes segments from CROP’s website.