The overlooked role of small fish to fight malnutrition

The Norad supported project “Samaki”, which means fish in Swahili, unites Norwegian researchers with colleagues in Tanzania to study how small-scale fisheries are the key to combat malnutrition. This is part of a bigger picture in the fight for scarce resources and on the question whether small fish should be used as food for humans or become fish food?

Main content

Samaki is a research and capacity building project led by UiT – the Arctic University of Norway with several partners from Norway and Tanzania. The University of Bergen (UiB) is a key partner in the project with Professors Jeppe Kolding and Ragnhild Overå involved. The project is financed for six years with NOK 20 million from the Norwegian Agency for Development (Norad).

“The marine biologist Ian Bryceson, who was previously a professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) and now emeritus, initiated the project. He and Jeppe have many years of collaborative experience, and this is how we got involved,” Overå says.

Realizing that Kolding also will be an emeritus in three years’ time, Jorge Santos and Jan Petter Johnsen at UiT’s CRAFT Research Lab were approached to lead the interdisciplinary project.

“The project covers a broad field of disciplines dealing with fisheries including biology, ecology, nutrition, livelihoods, gender and human rights,” says Overå.

Interdisciplinarity is key component

A central part of the research collaboration is educating master students, PhD candidates and postdoctoral fellows at the University of Dar es Salaam and in Zanzibar.

“You could say that the project covers the entire supply chain – from hook to cook – giving the students an opportunity to specialize along a broad spectre,” Kolding says, “the goal is building institutional capacity and we cooperate closely with local educators, many of whom have been educated in previous Norad projects. Tanzania’s national institute of marine research is also providing guidance as part of the project.”

This interdisciplinarity means that the candidates can choose between natural sciences and social sciences as part of the Samaki project.

“The project supports tuition and discussions on fisheries related activities. To widen our perspectives and provide updated knowledge. Our aim is basically to guide the students in the craft of writing a dissertation,” Overå says.

The project is strongly anchored in the UN 2030 Agenda and involves several of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“Fisheries are key to reach goal 2 – zero hunger, whereas nutrition is vital to reach goal 3 – good health and well-being. In general, goal 1 – no poverty – is an overall objective for the project,” says Kolding adding the gender dimension as a central part of the project, including goal 5 – gender equality – and goal 16 – peace, justice, and strong institutions.

An important partner for the Samaki project is the Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA), an organisation covering big parts of the Indian Ocean and where Bryceson was one of the founders.

Aiming for impact

Building on the SDGs the project aims to have impact with policy makers.

“Even before the project officially started, we could point to the success of having quite a few researchers from Tanzania involved, who have had their education funded via previous Norad projects. This demonstrates the capacity-building that Samaki will build upon,” Overå points out.

The project also includes non-research stakeholders from the small-scale fisheries supply chain in Tanzania.

“We have developed work packages covering all aspects of the supply chain as part of the project. Fishing at lower trophic levels is more and more common in Africa. The small fish caught are often sundried, which is very energy efficient. They are like small vitamin bombs,” says Kolding, “there is no fossil fuel involved in producing this food, which is cheap and available to poor people. It has clear parallels to our SmallFishFood project, where we aim to promote the value of small fish to combat malnutrition.”

Taking a critical look at Norwegian practices

The researchers also aim to look at how Norway conducts its small fish business, with small fish increasingly being viewed as some sort of poor man’s food.

“People no longer eat herring or anchovies in Norway. We want to turn the tables and show that small fish is much healthier than merely eating boneless fish fillets,” Kolding says.

“From a societal perspective, the small fish food industry from fisheries via processing to trade provides many people with jobs. This income also strengthens the food security of the people working in the small fisheries industry. Not only are they able to eat fish, but can afford an overall improved diet,” Overå says.

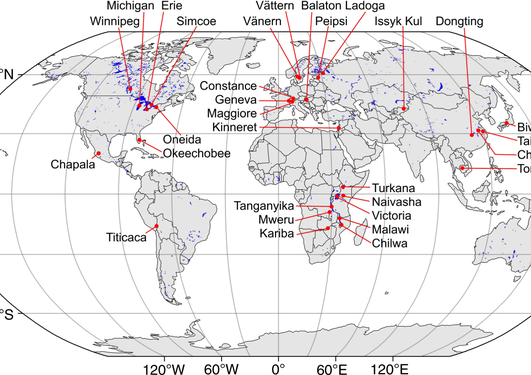

Kolding has worked on several small-scale fisheries research projects in the Caribbean, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Overå has specialised in small-scale fisheries in Ghana and is also partner in the interdisciplinary research project Urban Enclaving Futures, which is funded by the Research Council of Norway.

The Samaki project offers an opportunity to make use of previous observations and theories developed also from other geographical areas. Not the least Kolding and Overå look forward to studying the different parts of the supply chain in small-scale fisheries in Tanzania and Zanzibar.

Ocean laboratory on small-scale fisheries

Kolding, Overå and their SmallFishFood partner Marian Kjellevold from Norway’s Institute of Marine Research (IMR) will all take part in a selected satellite activity as part of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. This takes shape as an Ocean Decade Laboratory on small-scale fisheries in Ghana with input from Peru, convened by research assistant Christiana Naana Sam from UiB. This event will also bring together stakeholders from all parts of the supply chain and the researchers believe this ocean lab will also be of great value for the Samaki project.

“In Norway there has long been a debate on whether fish meal and fish oil (FIFO) should be used for human consumption or fish feed. This is a real dilemma. Now this discussion is attracting attention in Africa and Latin America as well. The fight for the small fish is getting harder with the arrival of big international actors who want to increase the production of fish feed from small fish. This is increasingly a human rights issue,” says Kolding.

Overå points to the Congolese market, which is important for Tanzania and Uganda’s small-scale fisheries, and thus relevant for both the Samaki and SmallFishFood projects.

“Rather than exporting small fish to fish meal factories it would be beneficial to export this fish to other poor populations across Africa. In Congo dried small fish is vital food for its largely poor population. If fish meal producers buy the small fish, however, it will end as salmon feed or chicken feed,” she says.

The fight for the small fish

Recently, Astrid Elise Hasselberg got her PhD degree at IMR/UIB with a thesis on the importance of small fish and PhD Candidate Fridah Siyanga-Tembo recently embarked on a project looking at how small-fish can be integrated in school food programmes. This has caught the eye of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), who are interested in how small fish can be used as an addition to meals offered to refugees to increase the nutritional value of their food consumption.

“There is a big and ideological battle for the use of small fish,” says Kolding.

- If you want to participate in the Ocean Decade Laboratory on small fish, you can read more on the programme and register here.