Changing seasons for New Zealand beekepers

As part of the CALENDAR project, several smaller research teams have investigated the seasons of beekeepers around the world, among them the New Zealand team.

Main content

The New Zealand CALENDARS team's experiences and findings on the seasons of beekeepers

The goal of our project was to contribute to the global CALENDARS project by assessing climate change indicators, changes in practices, and the outlook regarding beekeeping in New Zealand.

To accomplish this goal, we examined the influence of climate change on beekeeping in New Zealand; analyzed how beekeeping calendars have changed and how they affect beekeeping practices; and explored the dynamics surrounding beekeeping culture and economics.

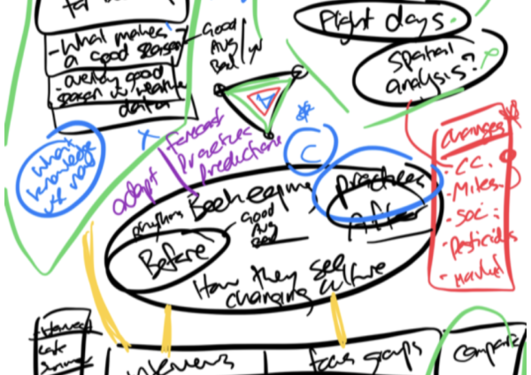

We field-tested hand-drawn calendars and sought to improve the Calendar Tool, a web-based tool used to gather seasonal perceptions. We conducted 11 in-person and virtual interviews with beekeepers in Wellington and around the North and South Island of New Zealand. We were also able to visit the Wellington Beekeepers Association beehives and observe the work of an experienced beekeeper up close.

Vulnerability to climate change

Our findings indicate interconnected influences on the practice of beekeeping with climate change, plant phenology, and bee activities. The direct effects of climate change, including increased rainfall and warmer temperatures, create uncertainty and vulnerability for beekeepers. More severe storms are making beekeepers increasingly vulnerable to climate change, such as Cyclone Gabrielle. This 2023 cyclone swept hives away by floods, setting beekeepers back by years. One retired commercial beekeeper identified that, "If there is one stark lesson for all beekeepers in New Zealand, past benchmarks on where it is safe to locate apiaries no longer apply". Without the past as guidance, beekeepers can only take an educated guess of what environments and locations will be safe, leaving their hives vulnerable to future climate disasters.

Phenological shifts create uncertainty

Phenological shifts due to climate change are also creating uncertainty for beekeepers. Phenological mismatch between bees and the flowering seasons result in further shifts, such as unpredictable honey harvests.

The most significant of these seasonal shifts relates to the threat of Varroa mites, which are parasites that feed on bees and weaken hives. Due to increases in Varroa mite populations, beekeepers must now add additional Varroa treatments to their calendars, which is expensive.

It is also becoming more difficult to treat at the proper times due to shifts in the honey harvest season, during which beekeepers cannot treat, and shifts in the broodless period, a time in which Varroa mite populations decrease. Varroa destructor is the biggest threat to beekeepers worldwide and almost all bee colony losses in New Zealand, apart from starvation, can be credited to Varroa mites (New Zealand Colony Loss Survey, 2022).

Four beekeeping seasons

We have discerned roughly four seasons in the calendars of New Zealand beekeepers from 10 hand-drawn calendars, interviews, and calendar tool submissions. The beekeeping year begins in August in New Zealand with population management, followed by honey flow and harvest, wintering down, and ending with a holiday for beekeepers. During population management, beekeepers deal with swarms and tend to the queen honeybee. There are lots of brood in the hive during this time as worker bees are created in preparation for nectar collection.

Then the honey season begins, which many beekeepers consider to be the busiest season of their beekeeping year. Wintering down follows as beekeepers are preparing the hives for the winter. During winter (May to July), beekeepers tend to go on holiday and have a break from their beekeeping duties before they begin again around August. Varroa treatment occurs throughout the entire year.

Utilizing hand-drawn calendars to collect calendar data offered a deeper insight into how people view the shape of the year, what they define a season to be, how they picture a calendar, and what indicators mark the changing of an event or season.

Honey production central to New Zealand beekeepers

The production of Mānuka Honey is central to the New Zealand beekeeping industry. The initial surge of Mānuka production in 2016 brought many changes to the culture of the industry. Social conflicts between beekeepers, such as encroachment, stealing, and sabotage arose due to the increasing demand for Mānuka honey.

According to beekeepers, the high profitability of Mānuka honey made them hesitant to share information about where they were locating their hives. New governmental regulations on honey export prevent beekeepers from mixing Mānuka honey with other types, like bush honey, causing honey prices to decrease to the point that some beekeepers are unable to continue in the industry (Mānuka honey testing, n.d.).

Beekeeping in New Zealand is slowly recovering from the crash in the honey industry, and beekeepers are beginning to share information again to help each other to thrive and preserve bee populations against the threats of climate change and varroa mites.

There are mixed attitudes in the beekeeping community towards what lies ahead, but one thing is consistent: New Zealand needs to have bees. Some people "don't think there's a sense of optimism in the beekeeping community in New Zealand at the moment" because of the severe threat of Varroa mites. Others are very confident, including a research scientist at NZ Plant and Food Research who said that the future "is bright. We may lose some colonies in the interim, but we will find a way. We need to have bees."