Maternal mortality more than halved

In some parts of the world maternal mortality is still high. CIH Professor Bernt Lindtjørn led a project that led to significant improvements in south-western Ethiopia.

Main content

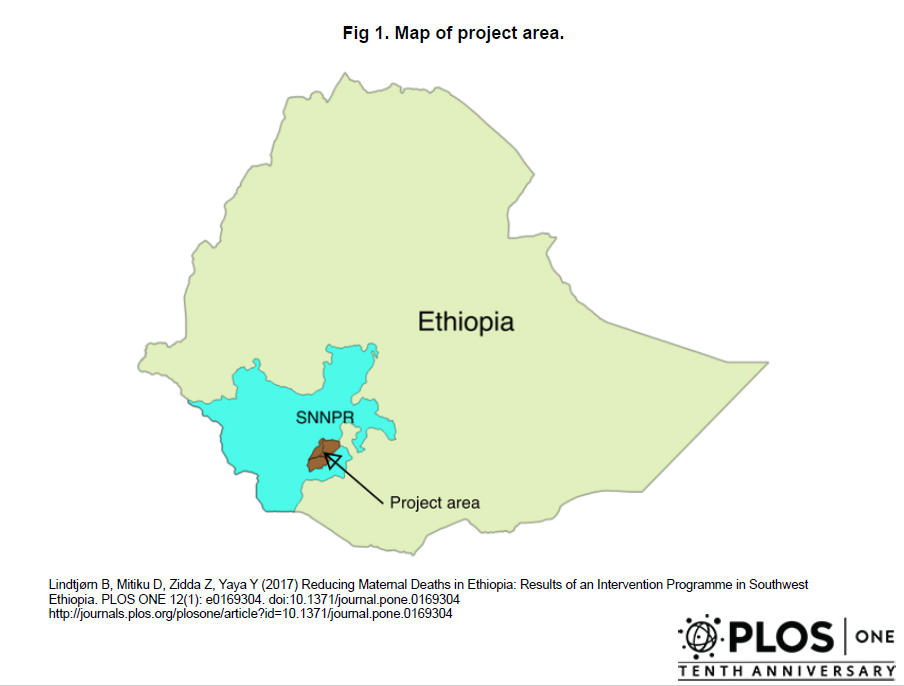

Centre for International Health (CIH) Professor Bernt Lindtjørn led a project in south-western Ethiopia (see map) studying how a number of interventions could reduce maternal mortality. Lindtjørn explains that there are several reasons why mothers die in childbirth (see Fact Box), but he highlights that the main causes are a lack of institutions and trained personnel as well as a lack of access (i.e. transportation) to services.

What is important about these two factors, according to Lindtjørn, is that it is possible to undertake relatively easy interventions to improve them. He underlines that it is not the women who should be blamed for not using delivery services but the fact that such services are not easily accessible or even available at all.

Substantial mortality reduction

The most important overall result of the project was that there was substantial reduction in maternal mortality: 64%.

This decrease was associated with increases in the numbers of trained staff, increases in the numbers of institutions undertaking CEmOC, increases in the numbers of mothers having Caesarean sections, increases in the numbers of antenatal controls and referrals, improved access to health service, decreases in the number of home deliveries and decreased use of traditional birth attendants.

The project’s main conclusion was that making standard delivery services available for all is the most important factor for improving maternal mortality.

Capacity building

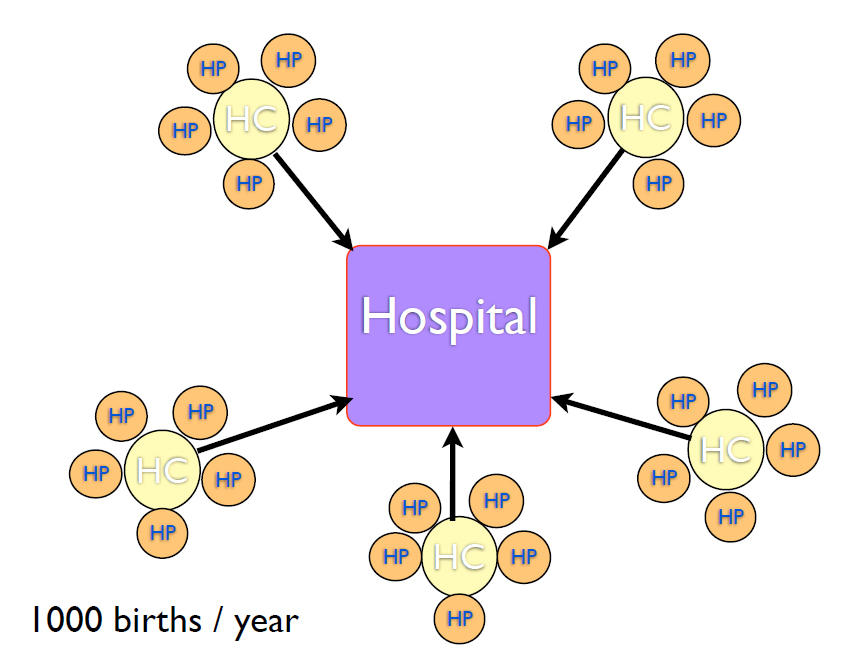

The goals for the project were straight forward and included making small hospitals available for rural populations, improving referrals (i.e. from health posts to health centres to hospitals when necessary (see image, right)), undertaking additional training for non-clinical physicians, nurses, midwives, and health extension workers, making essential equipment available, and supervising the health care services on offer.

Project participants conducted courses and engaged in specialised training. These included focusing on signal functions in the care being offered, encouraging the use of a partograph (a standardised schema for recording birth data, which also facilitates record keeping and potential data analysis), improving and teaching specific skills (i.e. use of vacuum), expanding and improving blood bank services, providing transportation services, introducing neonatal care and establishing maternity villages (where pregnant women from outlying areas could come pre-delivery).

Learning by doing

The project was based on the principle of “learning by doing” and involved short courses in Basic Emergency Obstetric Care (BEmOC) and Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Care (CEmOC), as well as anaesthesiology, scrub nursing and Continuing Medical Education (CME). It also included Master and PhD training in Public Health: one PhD and 6 master degrees resulted from the project.

Before the project started in 2008, Lindtjørn was involved in discussions with the Ministry of Health about training non-clinicians in CEmOC. The Ministry supported the project and covered its running costs, while NORAD and the Norwegian Lutheran Mission (NLM) provided the rest of the funding. The PhD and Master students were supported through the University of Bergen’s Quota programme.