Representing UiB in the Pacific

The ocean’s role for Earth was one of the key topics discussed at Our Ocean 2023 in Palau. UiB Professor Edvard Hviding was one of only a few researchers present at the conference and engaged in discussions on the Pacific’s role in climate change. But what would be the best measure to save our ocean?

Main content

Early January, the University of Bergen (UiB) was invited as one of only four universities globally to participate in the Our Ocean 2022 conference in the Pacific Island state of Palau. The invitation came directly from Palau's president, Surangel Whipps Jr, and the US Special Envoy for Climate, John Kerry. On behalf of University Rector Margareth Hagen and University Director Robert Rastad, Professor Edvard Hviding from the Department of Social Anthropology was asked to represent UiB at this high-level meeting.

Long experience in the Pacific

Hviding is a natural choice with his career-spanning research in and on the Pacific Ocean (since 1986) and since 2005 he has been director of the research group Bergen Pacific Studies. He has been a driving force behind bilateral cooperation between UiB and the University of the South Pacific and now leads the Toppforsk project Island Lives, Ocean States, funded by the Research Council of Norway. (See FACTS.)

Our Ocean took place in Palau during Easter 2022 and Hviding travelled with a greeting from UiB and Bergen with a message of the strong ocean focus of the university and the city, which was communicated in various sessions at the conference.

“There were participants from 70-80 states and more than 100 institutions, from UN level to civil society. Only four participating institutions were universities, with UiB being the only invited university from outside the US. Our special invitation is probably connected to the fact that UiB has worked closely with Palau,” says Hviding, who has represented Palau at UN headquarters in New York and has been an adviser to Palau's UN ambassador during a series of negotiations on the ocean/climate nexus. In addition, UiB's Camilla Borrevik has participated in Palau's delegation at high-level climate summits (COPs) for several years, while at the same time conducting anthropological fieldwork in the country.

“I would also like to mention that UiB arranged a visit to Austevoll for Palau's former president, Tommy Remengesau Jr, in conjunction with Our Ocean 2019 in Oslo. UiB is also known in Palau as an ocean university through our commitments on SDG 14 – life below water,” explains the Pacific scientist with reference to UiB's status on SDG14 for United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI) and the International Association of Universities (IAU).

Hectic preparations

Hviding found himself caught up in hectic preparations in the runup to Our Ocean. Not only was a creative itinerary to take shape, but agreements were also to be made about meetings and preparation of content for presentation in Palau.

“I was careful to stress that I was a delegate for UiB and not there in a personal capacity. Palau was already established as a field of relations for me, even though I had never visited the country before. The aim was to show UiB's big portfolio in ocean science, especially within the natural sciences, but also across all UiB’s faculties,” says the social anthropologist.

“I highlighted some of UiB's main initiatives, such as my own interdisciplinary Norway-Pacific Ocean-Climate (N-POC) project, where 25 PhDs will be trained at the University of the South Pacific in collaboration with UiB. This has also been approved as an official Ocean Decade Action as part of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. In addition, I wanted to highlight the EU-supported SEAS project, where 37 postdoctoral fellows will train to become the future marine research leaders of Europe. Our SDG14 work for the UN system was of course also duly mentioned.”

Close ties with Norway's MFA

Before and during his stay in Palau, Hviding also worked closely with representatives from Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), represented by Policy Director for Climate Change Georg Børsting, Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre's Special Envoy for the Sea Henrik Harboe, and the Norwegian embassy in Manila, which is also accredited to Palau. In recent years, UiB has worked closely with the MFA in various high-level arenas, especially for science-based advice on the ocean and SDG14.

Through this activity, UiB has also become good at maximizing content in a minimal amount of time, since posts in the UN system rarely exceed two minutes, which was also the case for many posts at Our Ocean in Palau. Along the way, Hviding also made sure to communicate his activity on behalf of UiB through social media platforms.

This is the second time the UiB researchers participates in an Our Ocean conference.

“The most important lesson from 2019 was perhaps the very special type of event Our Ocean is. “Everything” takes place in plenary session. Everyone is on the “inside”. If you are invited and have the right access, then you have access to everything. Within this “bubble”, there is free flow of all kinds of people. This means that this is a kind of “flat” structure that allows you as a professor or activist to slide around with heads of state and senior diplomats. Everyone circulates around and in Palau there was a constant flow of people in and out of the plenary rooms and the large outdoor areas. A flow between all types of category participants,” says Hviding and makes no secret of the fact that it is professionally interesting for him as an anthropologist to observe this free flow: “An incredible number of conversations are created by this relatively flat structure.”

Fair winds for the blue economy

At the same time, he sees clear difference between Our Ocean 2022 in Palau 2022 and Our Ocean 2019 in Oslo, where UiB co-arranged a side event with Norway’s MFA, UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) and Palau’s Mission to the UN.

“Our Ocean in 2019 in Oslo was more characterized by business, with an emphasis on the industrial aspects of the blue economy. This distinguishes Our Ocean from the UN Ocean Conference,” says Hviding.

“In Palau, the dominant perspective on the blue economy came from the large ocean states in the Pacific. They are on the frontlines of climate change and thus the ocean/climate axis got more space. High-level, politically strong panels discussed this axis, often also seen through the eyes of young people in relation to the ocean and climate and with representation of the islanders' own knowledge of the sea, so-called “indigenous knowledge”. In some panels, politicians, philanthropists and artists were strikingly in flux with each other, and art and politics merged into a higher unity. In general, I would say that there was much greater diversity in the panels this year than in Oslo three years ago. Something that not least came from the island states’ own energy.”

Restarting Pacific research project

This was Hviding’s first work related travel after the COVID-19 pandemic and a relaunch of his own research projects in the Pacific.

“I used this the opportunity to restart my Island Lives, Ocean States project, meeting Pacific politicians and diplomats that I hadn’t met for more than two years. It was a delight to hand out pamphlets on the N-POC project to representatives from the 15 countries from which PhD candidates will be recruited.”

He also noted that the debate about the role of the ocean for the development of the planet now is higher on the agenda for many. Not least, it is important to increase the level of ocean literacy.

“It was interesting that many people had finally learned that ocean is to be referred to in the singular and that we only have one ocean. Not least interesting since we were in the Pacific Ocean, the part of this one ocean that is today in the strongest geopolitical spotlight.”

Deep sea mining was a hot topic

Deep sea mining was a particularly hot topic at Our Ocean, which it will also be at the second UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon in late June 2022.

“There were very clear voices on this, in two dimensions: A moratorium linked to knowledge that must be met through active exploration in the Ocean Decade. Or an outright ban on the extraction of deep-sea minerals,” he says, before adding an anecdote.

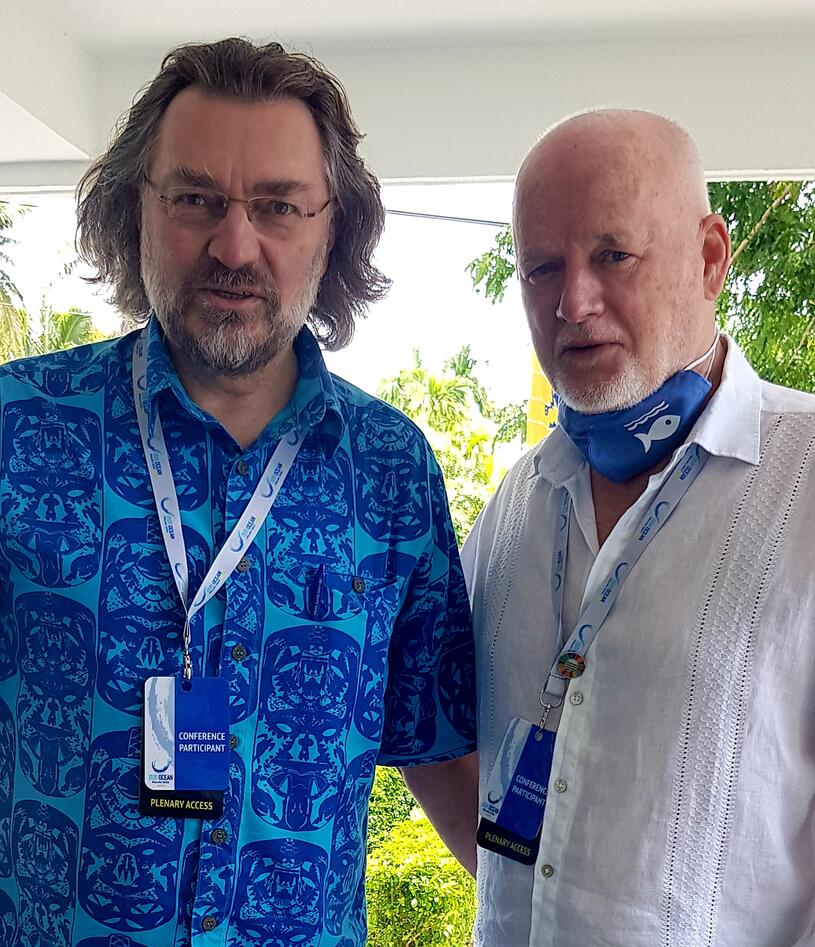

“I found it of particular interest that two of the world's richest ocean-interested philanthropists, Ted Waitt and Marc Benioff, were present (each via their private jet) at Our Ocean. When asked in plenary what was most important for securing the ocean's future, both stated: “A ban on deep sea mining”. But of course, there are many with other points of view. This becomes particularly complicated with the so-called green shift we are currently in the middle of. More minerals are needed for batteries and strong business interests will procure these from the seabed. This is a relatively intractable line of conflict that was brought up for constant discussion at the conference.”

During the conference, the small island state of Tuvalu, which is also one of the largest ocean states in the world if you measure its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in relation to the insignificant land areas, also released the news that they have withdrawn their political support for the extraction of deep-sea minerals.

Pushing forwards post Our Ocean

More than 400 commitments with binding support for ocean projects to an accumulated sum of about 16 billion US dollars were made during the conference.

“Some of these commitments were a bit strange, while others were more routine – especially from the rich states. It is difficult to see any consistency in the commitment portfolio, apart from the fact that many focus on the blue economy. Or maybe we should rather say extended blue economy, because now this must also be included in a sustainable calculation,” Hviding explains Hviding.

“I believe that quite a few of the rich countries, such as Norway, had relatively reasonable commitments. In other words, they give tens or hundreds of millions to various multilateral initiatives under the UN system. Or give something special to measures to clean up plastic. Or find new approaches to researching coral reefs or ocean acidification. So quite a few of the commitments that emerged were quite Pacific oriented.”

How will you make use of what happened at Our Ocean in your upcoming activities?

“First and foremost, I was able to restart the Island Lives, Ocean States project, which depends on ocean diplomacy and dialogue created through fieldwork in the Pacific. In a broader sense, the N-POC project has also gained an expanded meaning and meetings at the conference helped to make it flow better so that we are now ready to announce the project's 25 doctoral scholarships,” he says.