New Lancet report out: High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution

The report by The Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems, co-authored by leader in the GHP research group Ole Frithjof Norheim, sets a new definition for “quality health systems,” and finds that improved health system quality could prevent over 8 million deaths and improve the health outcomes of millions more each year in low- and middle-income countries. The report outlines actionable steps countries can take to revolutionize their health system quality in the SDG era.

Main content

KEY MESSAGES FROM THE REPORT

The past two decades have marked a “golden age”of global health, as the world has been able to significantly reduce mortality from maternal and childhood conditions and infectious diseases. However, methods of the past will not address the health challenges we currently face in the Sustainable Development Goal era, including remaining mortality and the rise of non-communicable diseases and injuries, withouthigh-quality health systems.

Health system quality is a determinant of health. Improving quality of care, and not only increasing access to care, is necessary for the success of the Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Health Coverage.

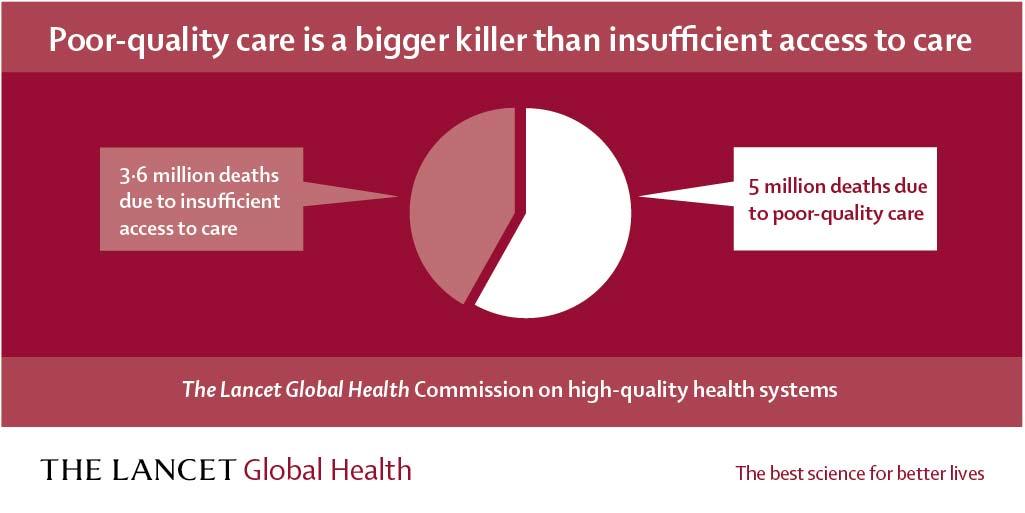

- Over 8 million lives were needlessly lost due to poor quality health systems in 2016.

- 3.6 million of these deaths were due to a lack of access while 5 million were due to poor quality.

- Each year, in 137 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), high-quality health systems could prevent over 2.5 million deaths from cardiovascular disease, over one million newborn deaths, and 900,000 tuberculosis deaths. Maternal deaths would decline by half.

- Health system amenable deaths led to $6 trillion USD in economic welfare losses in 2015, due to lost productivity.

High-quality health systems put people first. They consistently deliver care that improves health, are nimble to respond to changing needs, and engender trust among the populations they serve.

- Less than one quarter of people in LMICs believe that their health system works well. Populations that don’t trust systems in times of calm will not turn to them in crisis. Health systems cannot be resilient to shocks without quality.

At present, health systems in many low- and middle-income countries fail their communities. Good health care should not be a luxury only available to people in high-income countries or to the wealthiest in low-income countries.

- Too often, health providers do not follow basic clinical guidelines, omit routine screenings, fail to conduct necessary patient assessments. As a result, they commonly misdiagnose patients or prescribe inappropriate treatment. i. Across 5 Sub-Saharan African countries, 49% of providers can accurately diagnose pneumonia and 52% can diagnose diabetes.

- Poor quality is not just a function of individual providers. Health systems as a whole are struggling to provide competent care: they cannot guarantee safe procedures, timely care, referral, and care continuity for chronic disease. Primary care is underperforming, with many people preferring hospitals or specialists instead. i. Fewer than half of women delivering in a facility in 41 countries had a provider check on them within one hour of delivery, a critical window for detecting complications. Breast and cervical cancer and TB treatment is often delayed by many weeks. Surgical procedures result in infections for one in ten African patients.

- Vulnerable groups, including the poor, less educated, and those with stigmatized conditions, disproportionately receive poorer quality health care.

- Current health systems fail to treat patients with courtesy and dignity. i. About one third of patients have poor experiences with care, including disrespectful care, short consultations, poor communication or long wait times.

Creating high-quality health systems is not primarily a technical issue. Political commitment is needed first and foremost.

- When people trust their health systems, they tend to trust their governments. Leaders have a political incentive to improve health services.

- Countries are investing massive sums to roll out universal health coverage (UHC), but if they cannot deliver quality care, these promises will be empty and these programs will fail. A failed UHC strategy would derail efforts to reach health goals, waste resources, and deplete public trust.

- We will know the quality of health systems has improved when public servants choose to receive treatment from local facilities for themselves and their families.

THE OPPORTUNITY/RECOMMANDATIONS

How health systems are evaluated needs to change. We need to judge systems on performance, not inputs (i.e., number of nurses, number of clinics, doses of antibiotics).

- Measures should reflect the goals of high-quality health systems: competent care, patient experience, health outcomes, and confidence in the system—these are the core indicators of health system quality.

- Current global measures overestimate health system performance by reporting only coverage (contact with the health system). Countries should hold themselves to a higher standard by measuring quality-corrected or effective coverage.

Countries can take four universal actions to improve the quality of health services

- Govern for quality to establish and maintain a system-wide focus on quality i. Governments should set a shared vision, mechanisms for accountability, and strategies that both track what does and does not work and enable necessary shifts, putting its citizens first.

- Strategically re-organize services to maximize health outcomes, rather than maximizing access alone i. Complex services should be concentrated at higher level, higher volume facilities, while less acute, preventive, and continuous care should be provided by primary care clinics and in the community. This will not only improve outcomes but also health system efficiency.

- Modernize education of the health workforce and create workplaces that enable quality i. Current training models for doctors and nurses are outdated. Health workers require competency-based education that emphasizes problem solving, strong communication, and respectful treatment. Health system managers should demand excellent performance and create working environments to support it.

- Ignite people’s demand for high-quality care i. Public demand has driven improvement across many industries but has been overlooked in health care. People can put constructive pressure on health systems if they know what services they are entitled to, The Lancet Global Health (2018).what quality to expect, and that their feedback will make a difference.