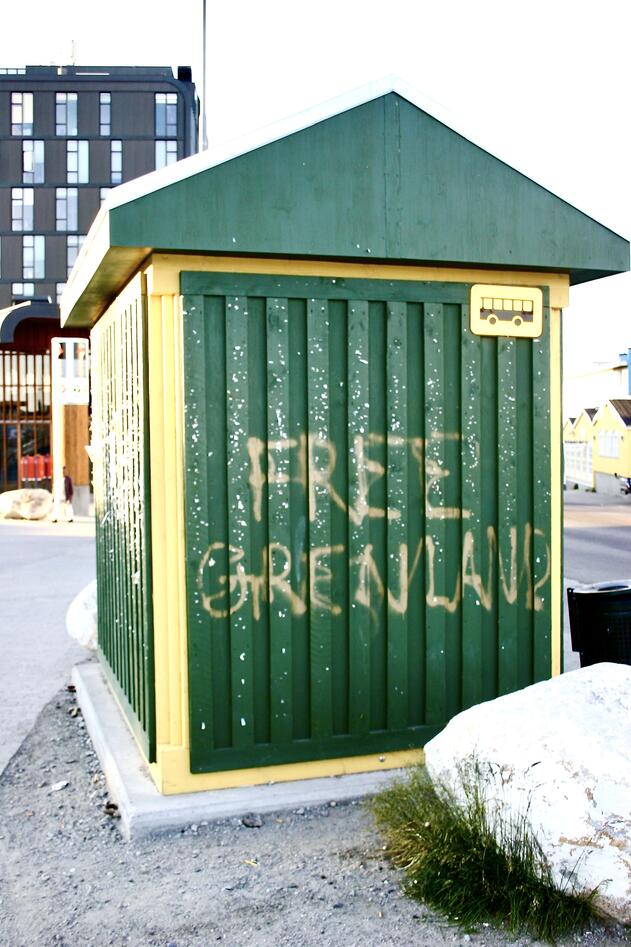

Will Greenland gain sovereignty?

Sampol scholars explore Denmark’s Inuit territory as it grapples with the prospect of statehood

Main content

One of Europe’s last colonies may soon declare independence – but first, its predominantly Inuit citizenry must resolve vexing trade-offs between protecting the Arctic environment, guarding Indigenous culture, and bolstering the island’s treasury. That’s what two scholars from UiB’s Department of Comparative Politics learned on a recent visit to Greenland, a longtime Danish possession that is wrestling with the possibility of statehood.

Professor Kristin Strømsnes and associate teaching professor Aaron Spitzer made the journey earlier this month, spending a week in Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, to meet with local officials, academics, and administrators. Strømsnes and Spitzer were part of a larger delegation representing Visions of the Arctic, a UiB research project and proposed "center of excellence" now in the final stages of consideration by the Norwegian Research Council.

In Nuuk, Strømsnes and Spitzer visited Greenland’s government headquarters, observing sittings of the Inatsiartut, or Greenlandic parliament. Formed in 1979, the body has won increasing responsibility over the island’s affairs, such that today its authority excludes only such matters as monetary policy, foreign relations, and defense.

Denmark has agreed to cede those powers, too, making Greenland the world’s first Inuit-majority country. But first Nuuk must find money to replace the current annual block grant from Copenhagen of roughly four billion Danish kroners.

That amount can likely come only from oil- or mineral-extraction. Thus, Greenlandic leaders have entered a divisive debate over how to balance financial autonomy, nature, and Inuit lifeways. Traditional political allies now often find themselves at odds on the issue of independence.

Other cleavages also divide Greenland, including the growing gap between remote villages and booming urban hubs, especially Nuuk. Among the issues under discussion in parliament was whether Greenland should follow Norway in providing Finnmark-style tax abatement and loan-forgiveness schemes to struggling rural settlements.

Strømsnes and Spitzer learned it is not just Greenland’s domestic politics that have grown complicated by the autonomy question. Visiting Greenland’s university, Ilisimatusarfik, they met with political scientists Maria Ackrén and Rasmus Leander Nielsen, who explained that Greenland, so long linked with Europe, is increasingly turning its international attention toward Canada and the United States.

Also at the university they heard from Anna Andersen, a Russian Sami scholar researching the impact of Denmark’s forced relocations last century of rural Inuit to Nuuk. Ostensibly conducted to modernize Greenland and improve access to jobs, healthcare, and schooling, the relocations are now recognized to have caused severe cultural and social disruptions.

Strømsnes and Spitzer met with photographer and artist Julie Edel Hardenberg and her husband Svend, formerly Greenland’s top bureaucrat and now both a leading Nuuk entrepreneur and star of the Danish hit TV series Borgen. And, as part of the larger Visions of the Arctic group, they met with officials from the Greenland National Museum and Archives, exploring ways to strengthen research connections with Bergen – which, from Medieval times to the 1700s, was the gateway between Greenland and Europe.

Knowledge and connections developed in Greenland will contribute to the Visions of the Arctic project, in which Strømsnes is a principal investigator. It will also contribute to the Sampol research project Indigenous People and Governance in the Arctic, of which both Strømsnes and Spitzer are core members.