"Tramspotting" i Oslo

I det siste blogginnlegget frå WAIT-prosjektet, bloggar Marry-Anne Karlsen om Ruth, ein irregulær migrant i Oslo.

Hovedinnhold

Gjennom Ruth drøfter Karlsen korleis irregulære migranter si erfaring av venting blir produsert, kvar den kjem frå, og korleis den blir levd:

Ruth and I are sitting at the tram stop, occupying the only seat. The stop is quite crowded, and more people are constantly coming. It is rush hour, and the tram is almost 20 minutes late due to traffic congestion. When it finally arrives, it is already quite full. Unlike the other people at the stop, we do not try to squeeze in. Two minutes later a new tram arrives, half full, but we are not boarding. As soon as it drives of, a third tram arrives, this time it is empty. Ruth and I share a laugh of all the people that squeezed into the first tram who could have had a seat if they had the patient to wait a few minutes. However, Ruth and I are not going anywhere. We stay at the stop, watching later the three trams pass by again on their return trip, with similar pace, the first one full, the second half full and the third empty.

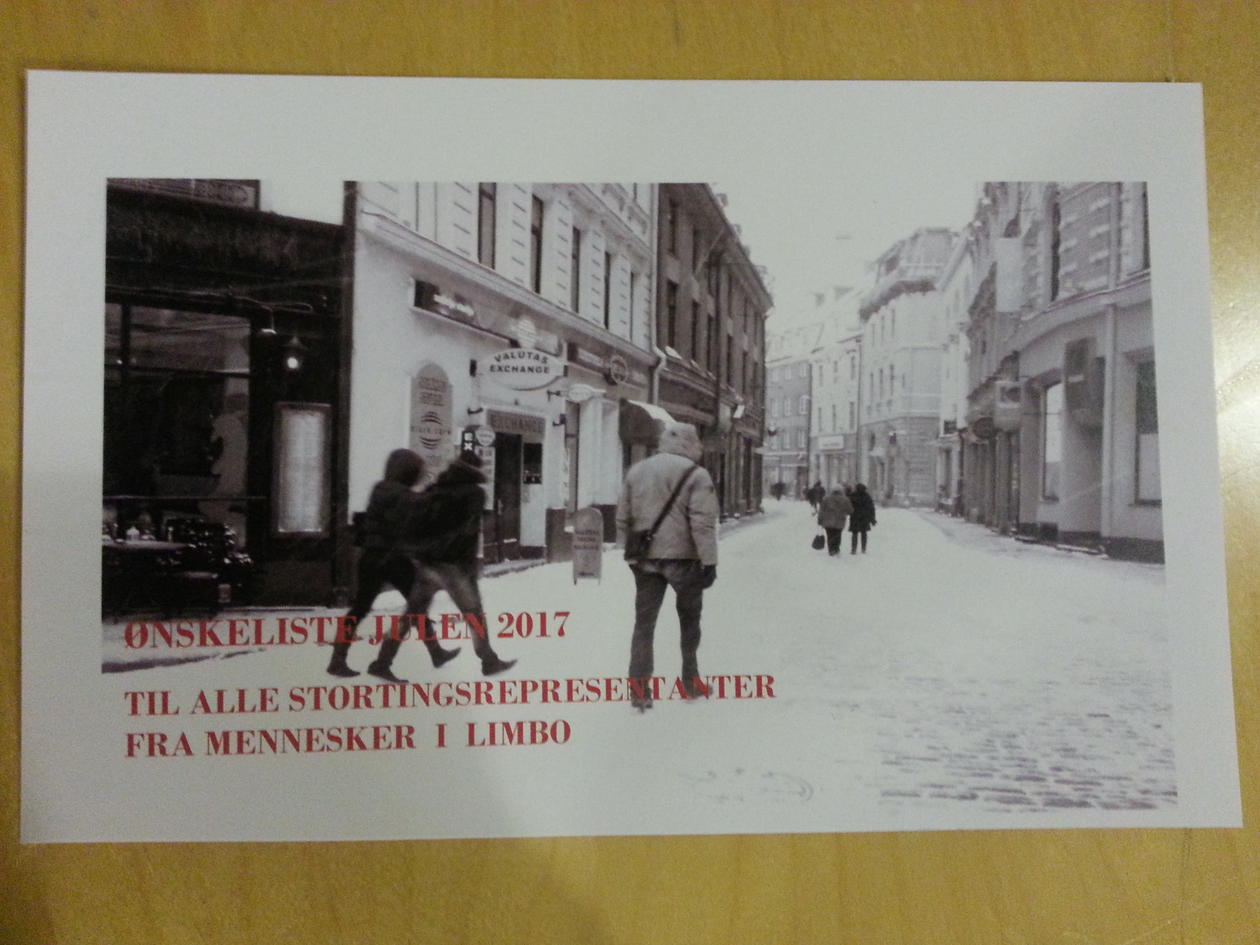

Waiting is something that is familiar to most of us. We wait for public transport, a medical appointment, a bureaucratic decision, or a late friend. Thus, one might argue that waiting is a prominent feature of modern life. Waiting, to be at the right place at the right time, also form an important part of ethnographic fieldwork. The term waiting is also frequently used to describe more prolonged and broader conditions of uncertainties, where people, most often the poor, the unemployed, migrants, are waiting for opportunities to realize life projects. In Oslo, for instance, the association of and for irregular migrants is called Mennesker i limbo [People in limbo]. In their brochure, they describe limbo as ‘an eternal waiting time’, experienced as ‘a condition of paralysis and hopelessness’. Their symbol is an image of people stuck in a bottle, unable to get through the narrow bottleneck. There is also an activist run Facebook page called Ventebarna våre [literally ‘our waiting children’]. Their stated purpose is to post stories about the faith of irregularized children ‘while waiting for political action’.

Using the term waiting for such varied situations as the short-term every day experiences, fieldwork, and the more prolonged conditions of uncertainty imply a sort of recognizable commonality between these phenomenon. Yet, it is becoming increasingly clear during fieldwork that experiences of waiting varies, and that it can be a slippery and sometimes confusing concept that masks differences.

Trying ‘to scratch the surface’ of prolonged waiting, as Shahram Khosravi put it in the previous blog from the WAIT-project, I try both to understand how this sense of waiting is produced, where it comes from, and how it is lived. My fieldwork therefore includes a lot of conversations with irregularized migrants, about how they see their past, present and future, as well as ‘hanging out’ to get an impression of how they spend their days.

‘What’s new?’

In my conversations with irregular migrants, they would usually relate waiting both to an experience of having their lives ‘put on hold’ by being excluded from significant social institution such as work and education, but also specifically to waiting for decisions by the immigration authorities. Most of the irregularized migrants that I meet during fieldwork are rejected asylum seekers that have received the so-called ‘final decision’ in their case. This means that they have had their case reviewed first by the Directorate of Immigration and then by an independent appeal board called UNE (Utlendingsnemda). Yet, they have remained in Norway, some for two, five ten, fifteen and twenty years. All of them have attempted to reverse the decision by filing a request for ‘renewed consideration’ [omgjøringsbegjæring] from UNE, often a number of times. As a rule, they must submit new and pertinent information or new documentation that supports their case for the immigration authorities to reverse their decision. Hence, ‘What’s new?’ is a question that troubles many of the irregularized migrants that I meet in Oslo. Some of them are constantly trying to find the new evidence that will convince UNE of their identity or political activities, anxiously waiting a reply or waiting for an appropriate time to pass before filing another request, trying new lawyers or saving money for a court case. Occasionally, someone succeeds, but most often, it is just another rejection. Others, have been through it enough times, placing their faith, at least for a while, in God, waiting for the system to change. As Dinha, an Ethiopian woman who has been in Norway for ten years, commented: ‘I can’t take another rejection. I will go crazy’. Waiting for the decision by UNE was something they all associated with increased level of stress and deprivation of sleep.

‘Forget our cases, give us our humanity’

I’ve frequently heard these words, or a variation of them, uttered by irregularized migrants. For many of them, the only answer to ‘what is new,’ is that they are still here. Reminding politicians of their continued presence, and plight, is one of the aims of Mennesker i limbo. During this autumn, they have been planning a manifestation outside the Parliament on 7th December. At the last couple of meetings, members have been preparing for this by writing a kind of Christmas card to each of the members of Parliament, stating their wishes. On top of most lists, is a residence permit. Also the right to work, education, healthcare, to learn Norwegian, and to be seen as fellow human beings, while irregular, are stressed.

Call for amnesty or regularisation measures for irregular migrants who have stayed for years have received little political support in Norway, due to the fear that it would encourage more to stay. Over the past decades, Norwegian authorities have also restricted rejected asylum seekers access to welfare and work in an attempt to discourage illegal stay. While it has not discouraged the irregular migrants that I have met, it does seem to have had a negative effect on their living conditions.

Ruth, the woman whom I went ‘tramspotting’ with, had been one of many who had been able to find regular work, paying taxes, until 2010. She had been issued a temporary work permit when she applied for asylum, and even when her application was rejected, the tax authorities kept issuing the work permit until the practice was discovered and stopped in 2010. Since then she has not been able to work, and is now homeless, like many of the other women I meet in Oslo. While they can generally sleep at a friend’s place, the days, they tell me, are often spent walking around the city. The day of ‘tramspotting’ I had been ‘hanging out’ with Ruth, walking around the city, visiting a few shops and shopping malls, looking at clothes on sales, but not buying anything.

For me, this was a good fieldwork opportunity, a way to ‘scratch the surface’ by hanging out and observing. Yet, it was also a very stark reminder of how even short-term waiting experiences are not necessarily equally shared. While we were ‘killing time’, waiting for a place that served free meals would open, my nationality and financial situation provided me with far more opportunities for what I could do while waiting. After walking around for a few hours, I tried to invite Ruth to a café for a coffee or tea. Most of the time, the rain had just been a drizzle, but it was getting heavier. Ruth, however declined, suggesting we could seek shelter at the tram stop. Luckily, the temperature had risen a few degrees above zero that day.