Framing cancer

CCBIO recently completed its CCBIO903 course Cancer Research: Ethical, Economic and Social Aspects, including a CCBIO Special Seminar, titled “Cancer in the news”. The course is quite unique on a global basis, and recruited participants with a great variety of backgrounds and of geographical locations, such as Bergen (CCBIO), Oslo (Oslo University Hospital, Institute for Cancer Research), London (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) and Boston (Boston Children’s Hospital).

Main content

Cancer research in a societal perspective

The 5 ECTS CCBIO903 course is part of the CCBIO Research School, and is co-organized and taught by three members of the ELSA and Economics groups in CCBIO: Roger Strand, Anne Bremer and John Cairns. Held four times since 2015, the course runs over two weeks and is a unique opportunity for PhD candidates - not only those who are part of CCBIO, but open to students internationally - to question the assumptions underlying their PhD work, discuss the robustness of their research, and anchor it in a broader social, cultural, political, economic and ethical context. The core of the course is structured around the volume edited by Anne Bremer and Roger Strand: Cancer Biomarkers: Ethics, Economics and Society (2017).

The teaching team is highly interdisciplinary. In addition to having a teaching team from different disciplines (philosophy of science, science and technology studies, and health economics), several guest lecturers are invited to share their perspectives. The attending students are also from different backgrounds and perspectives.

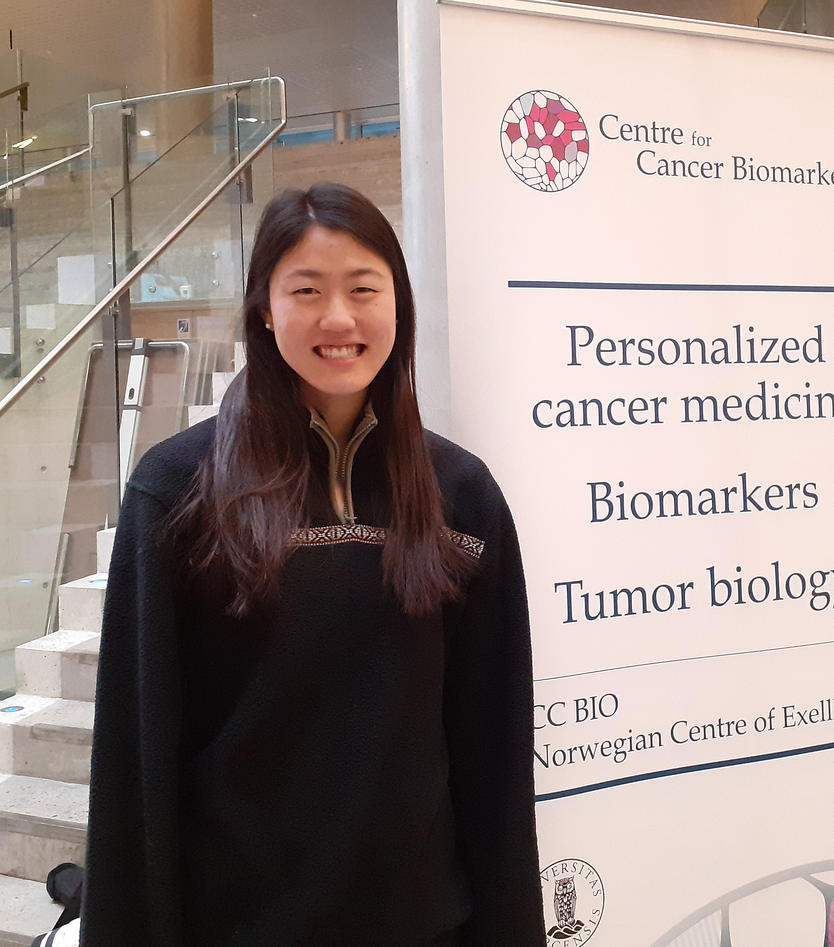

Inspired Boston medical student

Danielle Sim, medical student working in a cancer lab at Harvard/Boston Children’s Hospital, got interested in the course after attending the CCBIO/Harvard INTPART meeting in Reykjavik in August. There, she found herself intreagued by the social, ethical and economic discussions related to cancer research.

When attending the CCBIO course in Bergen, a few things stood out to her, compared to Harvard courses.

"The diversity of the students was rewarding," she says. "While I have been in very diverse classes before, I had never really interacted with students studying and living in different countries as well as different professions/PhD interests, such as clinical/basic science, medicine, nursing education, health policy/economics. I thought each student shared his/her own unique cultural and academic perspectives which promoted really productive discussions," she explains.

She also found that the multidisciplinary instruction from the lecturers, including philosophy, clinical science, economics, ethics and politics, explored precision medicine/cancer research from many different angles.

"This helped me as a student gain a broader understanding of precision medicine and cancer research in the context of society," Danielle reflects. "I also thought the instructors did a really good job connecting all of these issues regarding precision medicine and research together and creating a complete picture of the field," she says.

When reflecting on what she would bring home from this course, she feels that the biggest takeaway is that science, while demanding of respect in its own right, is incomplete.

"We cannot rely solely on science and data to make big decisions regarding health care and treatment – here are many other perspectives to consider including ethics, economics, politics, and the society's cultural landscape," she explains. "For my own personal interests, I particularly enjoyed learning about the history/philosophy of science from Roger Strand and how it became so vital in our current society today. It wasn't always this way!"

Danielle thinks the course has changed her thinking in medical research.

"From this course I learned the importance of direction and purpose in science. Science can cause unintended negative consequences, and it's necessary for scientists/researchers to consider their ultimate goals, motivations, and societal impact of their work before conducting research," she concludes.

Cancer in the news

The course rounded up with a special seminar on the 9th January 2020, open to all, with an expert panel who discussed in depth the issue “Cancer in the news”.

It invited a panel of four: Mille S Stenmarck, M.D. and B.A. (Honours) from the University of Durham, who has written her thesis (2018) on identifying frames around the issue of priority-setting and cancer in the media, Irmelin Nilsen, Research Assistant at the Department of Information Science and Media Studies, UiB, who has written her Master thesis (2019) on the interactions between sensation journalism and techno-scientific imaginaries around cancer research, Tine Dommerud, journalist specialized in health-related issues, writing for Aftenposten, the largest newspaper in Norway regarding paper issues and subscriptions, and Knut Helland, Professor at the Department of Information Science and Media Studies, UiB.

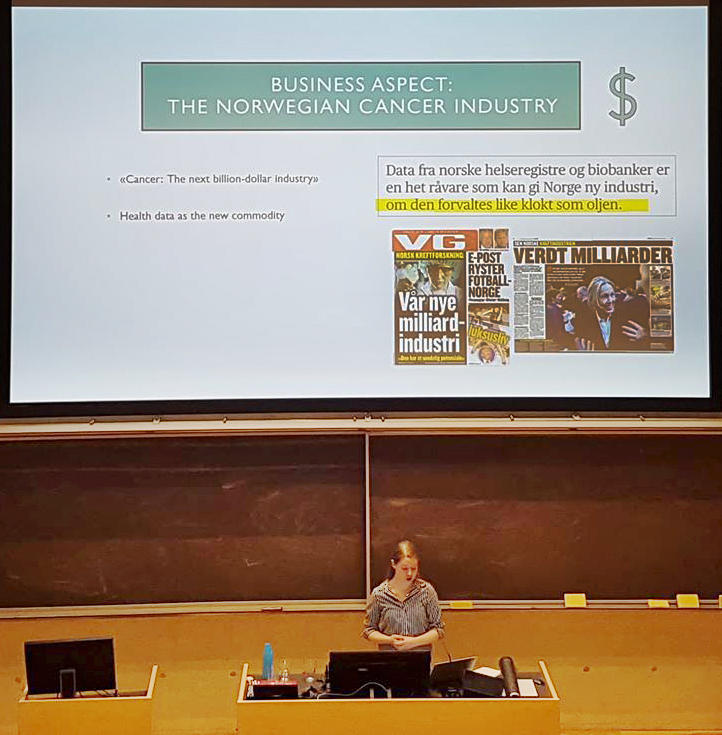

Media focus to a great extent on breakthroughs, hope and refusal of drugs

The panelists Mille Stenmarck and Irmelin Nilsen raised several points of reflection in their presentations. First, the dominant framings of cancer found in the news include those who convey great optimism towards cancer research – this field is often associated with ideas of ‘breakthroughs’, ‘hope’, ‘miracle medicines’ or even ‘cures’; and those presenting suffering cancer patients who are denied ‘life-saving’ medicines by the state.

Second, these framings found in the news come from ‘socio-technical imaginaries’ that are formulated by oncologists and other actors in the field of cancer research, where precision oncology is presented as a reality about to come true – it suffices to have the right technologies, enough funds and the political will to support that ideal.

Third, these framings are not only wishful thinking, but also shape the way society conceptualises cancer research and in particular precision oncology. They give the idea that there is no limit to what cancer research can provide. Precision oncology is what Callahan would call a ‘mirage of health’: hope and reality are being confused.

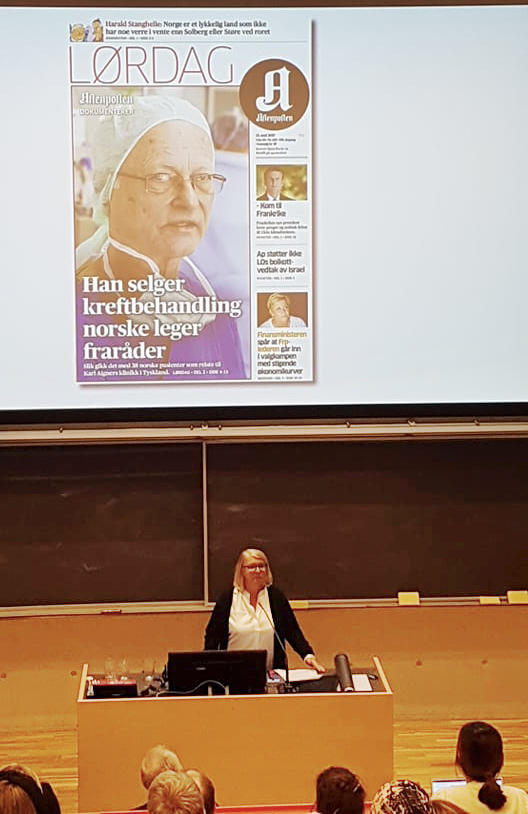

Journalists work within limits

Tine Dommerud from Aftenposten provided some explanations as for why these framings of cancer are strongly present in the media, by uncovering some of the constraints that a newspaper has to work with. There is the assumed interest of the readership for stories that bring hope, and the difficulty to ‘sell’ a story when it doesn’t start from an individual’s experience and struggles. There are also limited budget and time, which means that some important and meaningful issues (like the pricing of drugs) are outside the scope of newspaper articles. Finally there is the tyranny or ‘power of goodness’, by which when something is assumed to be ‘good’ (precision medicine for instance), then it is extremely difficult to build a robust critical argument against it, that will not be rejected straight away by the readers.

A social responsibility

The diversity of backgrounds of the panelists allowed for a unique debate to critically reflect on how cancer today is framed in the media, whether this is a responsible media discourse, and what impact hope, enthusiasm and optimism have on society. This is a first step towards what Mille Stenmarck and Irmelin Nilsen argue for: ongoing, critical debates across society, science, politics and the media on what responsible framings of and discourses around cancer are and should be.

We can all consider our own role in implementing this kind of responsible discourse.