3D-printing live tumors in vulvar cancer project

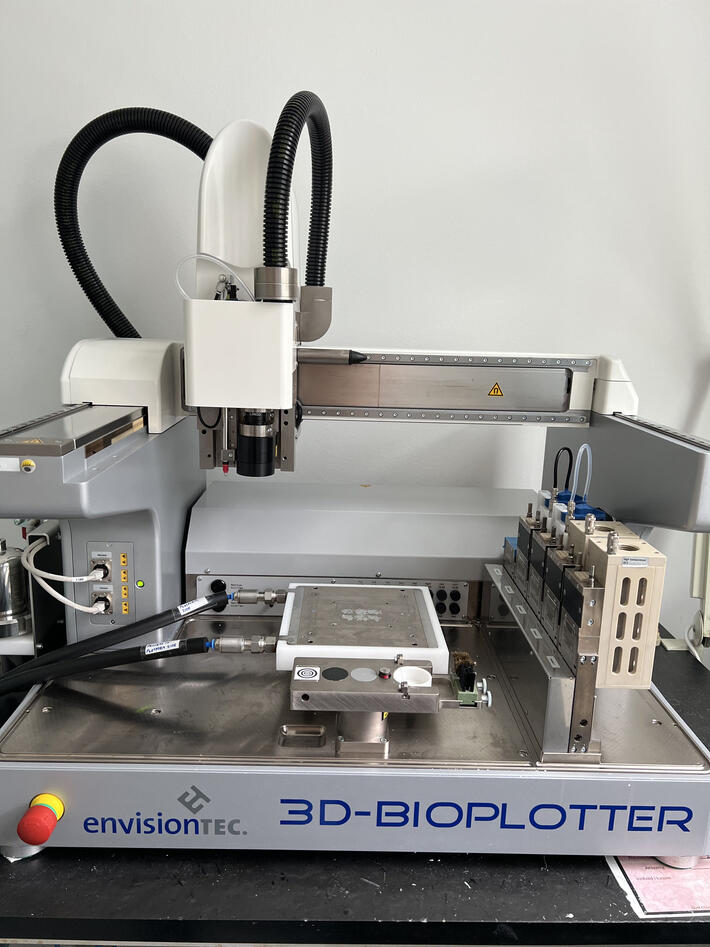

A collaboration project on vulvar cancer between the Bjørge, Costea and Mustafa groups are using a 3D bioprinter to print tiny vulvar cancer tumors with live support tissue, for more realistic testing of which therapy will give the best response.

Main content

A 3D bioprinter creates 3D shapes layer by layer using a digital CAD file as a blueprint. Instead of using plastics and metals, a bioprinter creates precisely engineered tissue structures from substances known as bioinks, containing living cells as well as viscous materials like alginate or gelatin. This allows the printer to produce 3D printed organs or – as in this case – tumors for use in research. Bioinks can contain differentiated cells (specialized, function-specific) or stem cells (nonspecific, later induced to become differentiated).

Tabooed disease

“Vulvar cancer is a serious disease, which, unfortunately, has not been subject to sufficient research. It is difficult to obtain representative models of vulvar cancer that can be used to test drugs. Because of the support from among other Sanitetskvinnene, we are one of the few research groups in the world working on this,” says Rammah Elnour, PhD Candidate at the Center for Cancer Biomarkers (CCBIO), University of Bergen. This project is part of Elnour’s PhD work.

Vulvar cancer, a disease that occurs on the outer surface area of the female genitalia, is a painful disease, and unfortunately with symptoms most women find difficult to talk about. Five years after diagnosis, 4 out of 10 would have died from the disease. Vulvar cancer is rare, in 2021, 119 women in Norway were diagnosed, and 45,000 worldwide. However, the incidence is increasing, and vulvar cancer has been associated with some types of HPV virus and the skin disease lichen sclerosus.

More targeted treatment

Elnour explains that 3D printing of mini tumors can solve a major problem in cancer research; that there is often a big difference between the results of therapy tests in the laboratory and the actual effect of the therapy on patients. Cancer cells grown in dishes or cancer in mice in the laboratory react differently to drugs than a cancerous tumor in a human body.

Many drugs appear to work when tested in laboratory studies, but do not work when tested on humans. There are several reasons for this; cancer cells in the body are not isolated as in a laboratory dish, and they are normally affected by the environment they grow in. They are, among other things, surrounded by support tissue and immune cells, and the interaction with these cells regulates how the cancer cells respond to chemotherapy. By printing mini tumors with cancer cells, support cells and inflammatory cells, cancer is formed that looks much more like vulvar cancer as it appears in the patient. Therapeutical interventions can thus be tested in a much more realistic way.

Important breakthrough

The researchers use cells from patients and have recently managed to use normal mucosal tissue from the vulva to develop a bioink, a gel, for the printing. This is a gel with living cells, that stiffens over time, and where cancer tissue can grow as in the body. The team has now just verified that cancer cells and other cell types interacting with the cancer cells will survive and grow in the gel.

“This is an important breakthrough. We have been adapting the gel so that it reflects the surroundings of the tumors as close as possible, and we are very excited to have succeeded,” Elnour explains.

The next step is to use the gel and the various cell types to print what are called organoids, small living models of vulvar cancer tumors.

"This is completely new and has only succeeded with a few other cancers so far," Elnour says.

Will save more patients

When the mini tumors are ready, the researchers will test whether they respond to drugs in the same way as cancer in patients. If successful, testing drugs and other therapies will be much easier, and not least save patients from time loss and adverse effects in unnecessary testing. The mini tumors can be used both to develop completely new therapies and to test whether existing therapies for other cancers can have an effect on vulvar cancer.

"It may very well turn out that there are already drugs that can help these patients better," Elnour says.

The experiences from developing organoids with vulvar cancer may be useful for other research groups worldwide, as there are many who are attempting similar studies with other cancers. So far, very few have succeeded in using bioprinting to create such mini tumors.

“We are at the forefront, and this research can save many lives in the years to come. I am very happy to have the opportunity to work on this,” Elnour concludes.

See this story in Norwegian here at Sanitetskvinnene.no.