What is algorithmic narrativity?

Stories are no longer exclusively a human domain.

Main content

"Television has changed the world!" Or did it?

In 1990 Raymond Williams argued that it was really the other way around: the world wasnt ready for the changes television would bring until a specific point in history. Even though the technology behind it would have been possible to create earlier, the world lacked the necessary social and economical foundations for television to be a success.

In an article in Dialogues on Digital Society Scott Rettberg and Jill Walker Rettberg expand this idea to our digital technologies and aesthetics, using a central CDN term, algorithmic narrativity:

"We take this one step further and argue that the introduction of new technology depends not only on science, social structures, and economic systems, it also depends on aesthetics. And the aesthetics of today's digital technologies are algorithmic."

Algorithmic narrativity describes the interplay between human understanding of stories and computer processing of different kinds, the idea that storytelling is no longer the exclusive domain of human beings. Algorithmic narrativity is central to the DNA of the Center of Digital Narrative (CDN). Algorithms now shape our stories in many ways, including social networks, where they affect the discourse and curate our memories, in video games where we play with algorithmic systems and of course with generative AI.

From mechanical to electronic authors

The first mechanical poetry generator, John Clark's "The Eureka", a machine that gave you small verses in Latin, came as early as 1845, which shows that algorithmic creativity is not entirely new. Nevertheless, it was quickly forgotten. Perhaps it was too early for its time? (See it in use here.)

Raymond Williams might attribute the machine's lack of success to the lack of an established social and economic foundation. Even a media technology we take for granted today, like cinema, struggled at first to find a socio-economic basis. Cinema went from being an exotic "sideshow" to serious culture to becoming part of the mainstream when traditional theaters changed and adapted to the distribution of film reels,. In the 19th century the flourishing book economy had no place for poetry generators.

Despite the setback, the aesthetics of algorithmic narrativity persisted. In the 20th century, poets and writers explored procedure-based and restrictive writing methods. From Dadaist writers' cut-up techniques to the OuLiPo group's intricate textual restrictions, algorithmic thinking governed a small part of human creativity. Computers as autonomous literary machines fascinated thinkers. In 1949, Geoffrey Jefferson argued that machines could not create sonnets, unless they could be based on "thoughts and feelings". Alan Turing replied that they would probably be able to do that - although he also pointed out that the people who would appreciate this the most were probably other machines.

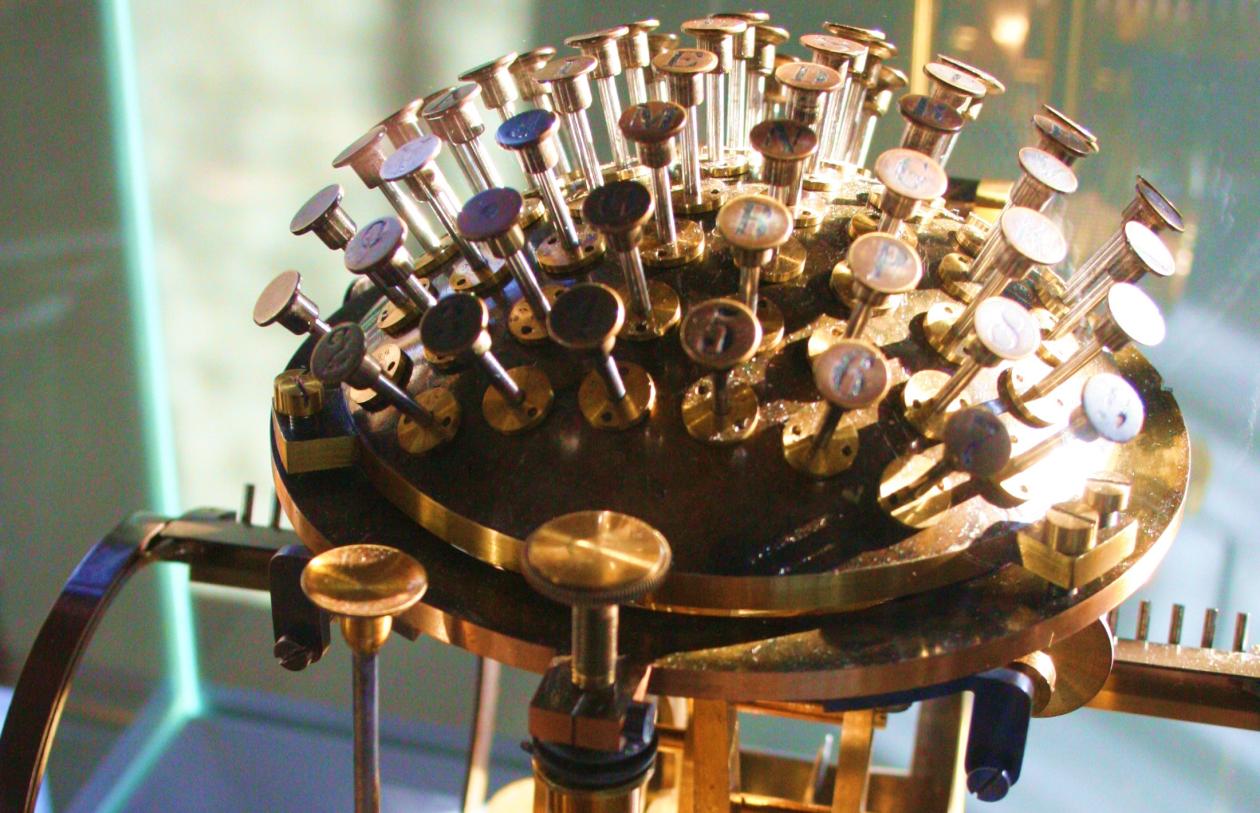

One of Turings colleagues, Christopher Strachey, created the first work of electronic literature in 1952:

"This was a slot-style poetry generator that randomly combined different phrases, adjectives, nouns, and pet names within a set grammatical structure to produce love letters that can be interpreted as simple jokes or as poignant parodies of the heterosexual courtship conventions that Strachey and Turing, as gay men, were excluded from."

With time came more complex generative literary systems, based on more advanced algorithms. Todays generative artificial intelligence, trained on large language data sets, produces cohesive results – whether we call it intelligence or not is based on our definition of intelligence.

Cyborg authorship – AI as co-writers

Technological changes bring gains and losses. Nietzsche's transition from handwritten manuscripts to typewriters changed his writing style, to shorter sentences. Writing technologies affect memory – whether it is pen and paper, books, typewriters or digital computers.

Algorithmic narrativity implies a fusion of meanings exchanged between humans and algorithms, rather than technological determinism. Today, the same debate continues around generative AI, which still needs a human hand on the wheel to be able to create complex literary works. Collaborative writing between humans and AI – cyborg authorship – shapes new genres within digital literature.

While the early days of the internet became a revolution in ways of communication with people around the world, social networks today are a driving force of commercialising communication, raising concerns of surveillance capitalism.

In the wake of the sudden growth of AI, the consequences for stories and society are still uncertain, the authors write.

"But we can be sure that algorithmic narrativity will continue to transform our society."

Reference

Rettberg, S., & Rettberg, J. W. (2024). Algorithmic narrativity: Literary experiments that drive technology. Dialogues on Digital Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/29768640241255848