Normativity in Nature: The Prospects of Re-enchantment

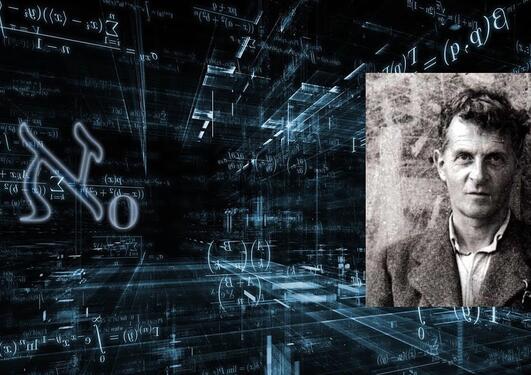

The framework for this workshop is provided by John McDowell’s reading of the later Wittgenstein.

Main content

The framework for this workshop is provided by John McDowell’s reading of the later Wittgenstein, in particularly the idea that a nest of interrelated normative concepts such as rationality, language, meaning, understanding, conceptuality, and Culture are resistant to “sideways-on” or “baldly naturalistic” explanations. At the same time as he resists certain forms of naturalism, however, McDowell admits the obvious tension between his perspective with the fact that there was a time when there were no rational agents at all, and that conceptual normativity therefore is somehow connected to the evolution of human beings. The workshop will take this tension as its basis.

Program

Day 1

9.00 – 9.30 Kevin Cahill: Introduction and Background to the Workshop

9:30 – 11.00 Francesco d’Errico: Human Cultures. Outcome of a Cognitive

Revolution or a Gradual Niche Construction?

11.00 – 11.15 Break

11.15 – 12.45 Henrike Moll: Shared Intentionality: A Transformative Account

12.45 – 14.00 Lunch

14.00 – 15.15 John Dupre: Emergence in a World of Process

15.15 – 15.30 Break

15.30 – 17.00 Joseph Schear: Human Mindedness: A Realistic Transformative

Alternative.

19.00 Dinner: To Kokker

Day 2

9.00 – 10.15 Danielle Macbeth: The Metaphysics of Emergence: Lessons from

Language

10.15 – 10.30 Break

10.30 – 12.00 Martin Gustafsson: Rational Wolves and Lion Talk

12.00 – 13.15 Lunch

13.15 – 14.45 Pirmin Stekeler-Weithofer: Full Language and Practical Forms:

On Presupposed Steps in the ‚Evolution‘ of the Human Mind

14.45 – 15.00 Break

15.00 – 16.30 Aude Bandini: Medical Diagnosis: Natural Kinds, Social Norms,

and their Interactions

18.45 Dinner at Knut Fægris hus

Abstracts

John Dupre, “Emergence in a world of process”

Long ago I wrote about reductionism, and why it didn’t work. If the properties or dispositions to behave, are not reducible, that is fully explainable by appeal to properties of its constituent parts, they are emergent. Then, I supposed that this was just a brute fact, not susceptible to or requiring any further explanation. More recently I have come to believe that the world is composed entirely of processes. Where there are what seem to be persistent things these should be understood as stable or better, stabilised, processes. Such apparent things, in fact, emerge from the surrounding web of process. In this talk, I shall explain why this emerging also implies the more traditional sense of “emergent” sketched above.

Danielle Macbeth, The Metaphysics of Emergence: Lessons from Language

When tasked with addressing the phenomenon of emergence, philosophers have generally taken one or other of two approaches, either a reductive naturalist approach that explains emergence away or a quietist therapeutic approach that affirms that things, paradigmatically, living things, can and do emerge but denies any possibility, or need, of explaining their emergence. To an outsider both would seem to be partly right, both the quietist insofar as there do seem to be emergent entities and the reductionist in taking it that some sort of philosophical account of emergence is needed. What the outsider wants, then, is a diagnosis of the appearance of incompatibility between emergence and philosophical explanation, to understand why the philosophical difficulty emergence poses takes the shape it does. My aim is to achieve such an understanding, and also to take the first steps toward an adequate account of the metaphysics of emergence, an achievement that is possible, I will suggest, through some reflections on language.

Henrike Moll, Shared Intentionality: A Transformative Account

The “shared intentionality thesis” states that the most distinctive feature of humans is their ability to share experiences with others in collaboration and joint attention. The original version of this thesis claims that children cognitively “become human” at age 9 to 12 months, when infants start to jointly attend to objects in their surroundings with other persons (e.g., Tomasello et al., 2005; Tomasello, 2018). In my talk, I introduce an alternative version of the shared intentionality thesis—articulated by Kern and Moll (2017)—according to which “shared intentionality”, rather than denoting a special capacity, primarily refers to a uniquely relational and social form of life. In tracing the ontogeny of shared intentionality, I will show that there is no particular moment in which shared intentionality is acquired. The transformative version of the shared intentionality I will defend maintains that humans are uniquely relational beings from the beginning of life; what develops across early ontogeny is the complexity of the acts of shared intentionality in which a child can participate, but some participation in this shared form of life is present from the start.

Pirmin Stekeler-Weithofer, Full Language and Practical Forms: On Presupposed Steps in the ‚Evolution‘ of the Human Mind

Kant’s transcendental logic is the result of subjective reflections on the conditions of possibility to think about present objects. Hegel transforms it into an explication of steps that allow us to talk about possible objects and their real instantiations. Full language encodes the conceptual knowledge necessary for any access to modalities about physical things and their movements (1), chemical matter and processes (2) and, finally, life on earth (3). In the emergence of the ‘personal’ form of human life there are developments that lead (4) from the social behaviour of animals to the human forms of practice, (5) from signal-languages to full language with its two syntacto-semantic parts of sentences, noun-phrases and verb-phrases, and (6) from enactive perception to conceptually formed apperception and intuition. Our mind thus depends on the shared intellectual and ethical history of whole humankind. We express the genericity of these developments by relating trans-subjective ‘spirit’ to ‘the concept’ in the sense of the indefinite system of definite, hence limited, conceptual domains to talk about and refer to – such that there is no further need for a divine creator nor for attributing to cosmic matter a disposition for evolving life and consciousness.

Aude Bandini, Medical Diagnosis: Natural Kinds, Social Norms, and their Interactions

According to the dominant view ("hybridism") in the philosophy of medicine, a condition can be considered a disease only if it involves both a bio-physiological dysfunction and a negative social assessment that harms the individual. However, this dual definition is of little help when the issue of medicalization is raised, that is, when we ask whether a given body state or behavior should legitimately be framed as a medical issue and dealt with accordingly. Here, I will focus on the case of overweight and obesity. According to the WHO and most public health agencies, obesity is a serious chronic disease, while overweight is an important risk factor for serious cardio-metabolic illnesses. However, it has been argued that to a large extent the criteria used to define them are arbitrary and motivated by moral and social prejudices rather than sound biological facts. This debate has recently been reignited by the arrival of new drugs (e.g. Ozempic® and Mounjaro®) whose efficiency in terms of weight loss can equal that of bariatric surgery while being much less risky. In principle, this should have no influence on our answer to the question of whether or when overweight and obesity are diseases or health-threatening conditions; it is, the argument goes, a mere matter of biomedical science and human physiology. However, according to the hybridist view, how people feel and what they experience also legitimately contribute to defining what diseases are. Now, in the case of overweight and obesity, conflicting claims have emerged: whereas some have argued for the demedicalization of larger bodies, a growing number of others advocate for an increased access to these brand-new weight-loss drugs, leading to a tremendous surge in demand. I will argue that this may influence our definition of obesity and overweight. Moreover, pharmaceutical marketing is likely to exploit this debate through a form of disease-mongering, which risks reinforcing questionable prejudices rather than promoting public health.

Martin Gustafsson, Rational Wolves and Lion Talk

According to Wittgenstein, if a lion could talk, we would not understand him. More recently, Michael Thompson has made the seemingly more radical claim that a rational wolf would not even be a wolf! I discuss both these examples to explore if there is a sensible and illuminating version of John McDowell’s distinction between first and second nature. Crucial to my discussion is the question whether McDowell’s distinction can be made sense of without presupposing some version or another of what Matthew Boyle calls an “additive” theory of rationality. I also consider how the social nature of language matters to the distinction’s philosophical usefulness and viability.

Joseph Schear

How should we understand our capacity for responsiveness to reasons as reasons? The rationalist view understands this capacity as transformative of the nature of human mindedness. The naturalist view, by contrast, understands this capacity as a new trick evolution has given us to cope with our environment. The paper proposes to reconcile these opposing views by sketching a position that accommodates the truth in each.

Francesco d’Errico, Human cultures. Outcome of a Cognitive Revolution or a Gradual Niche Construction?

In my presentation,I will summarize, building on my past and ongoing work, archaeological evidence for the emergence of complex technologies and symbolic practices in Africa and Eurasia. This review will show that cultural innovations emerged at different times, in different parts of the world, among different populations, including so called archaic hominins, and some of them were lost and reacquired later on in different forms. The timing, location, and pace of innovation appearance is inconsistent with scenarios attributing the emergence of “modern” culture to a biological event giving rise to our species in Africa. Rather, the evidence supports a model where cultural innovations stem from a multitude of interconnected, dynamic factors, both environmental and social. This process can be seen as an extended form of niche construction, where the constructed niche includes social, symbolic, linguistic, and institutional dimensions. This process is the outcome of complex and non-linear population dynamics and cultural trajectories that need to be understood and traced at a regional scale. As a consequence, it becomes essential to focus our attention on the conditions and mechanisms that may have triggered cultural innovations and on the factors that have enabled them to be preserved and disseminated. Among those factors special attention should be given to shifts in modes of cultural transmission that could have played a pivotal role in fostering cumulative cultural development.