Analysing microplastics in seafood

"Politicians need proper advice and that is where we as scientists need to contribute as active researchers and communicators", says Tanja Kögel, a researcher at the Institute of Marine Research, and the Department of Biological Sciences at UiB.

Main content

Can you briefly describe yourself?

Since 2015 I led food safety surveillance projects on contaminants in seafood, first at NIFES, 2018 fused to the Institute of Marine Research such as heavy metals and POPs. In recent years, I widened my horizon from that work with accredited, established methods towards leading the development of new quantitative analysis methods and a clean laboratory for small microplastics in seafood. That is both especially interesting and tricky as compared to other contaminants, as, in addition to chemical composition, particle size plays a role for uptake, toxicity, and analysis method development.

Earlier, I worked as a cell biologist and biochemist and advanced microscopist with unravelling intra- and intercellular transport mechanisms, also in connection with the endocrine system, specifically with the maturation of neuroendocrine granules and tunneling nanotube mediated transport. This provides me with a solid basis to new aspirations: investigating uptake and toxicity mechanisms of plastic particles, in precisely those combinations which we detect in the actual organisms in the environment.

Why do you do research on plastics?

Plastics problematics are a global threat to all life. It is also a very interesting socio-economic challenge highlighting global inequality and even interacting with climate change. Plastic is littered, and degrades very slowly in the environment. Clean-up of microplastic – everything in sizes such as pearls, bags, ropes or fishing gear is not sustainable in the long-term and definitely not in remote areas and deep ocean - yet it is transported there. Clean up of small microplastics and nanoplastics is close to impossible. Those particles cross body barriers like the intestinal lining, blood-brain barrier and placental barrier, and enter blood, lymph and tissues. In laboratory experiments, they were shown to cause many adverse effects, such as inflammation, energy storage and availability problems and reduced offspring.

Additives to plastics, such as plasticizers, biocides and flame retardants are known endocrine disruptors. We have no means of quantifying them with acceptable measurement uncertainty yet, and therefore are unable to assess the risk properly, as risk being a combination, of exposure magnitude, likelihood and severity of effects. Yet this contaminant has already infiltrated all ecosystems. We need to focus our energy in closing the tap, in parallel to developing suitable surveillance. Waste management is pivotal. However, there is no one solution to the problem but actions and management along the whole value chain of plastics are necessary, to use this fantastic material to its positive potential without paying devastating hidden costs to our ecosystem and human health. This responsibility cannot be left to consumers or industry alone, political incentives are necessary at the right levers. Politicians need proper advice and that is where we as scientists need to contribute as active researchers and communicators.

Could you describe your ongoing projects?

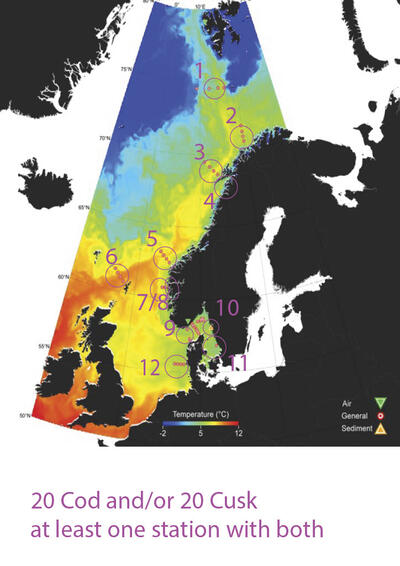

JPI Oceans finances FACTS (Fluxes and Fate of Microplastics in Northern European Waters), which is a transdisciplinary, multi-national effort to connect quantification of microplastic in the matrices air, water, sediment and commercially important fish species (see circles in figure for planned sampling stations) from Germany throughout Norwegian waters up to Arctic region with a modelling effort with to aspiration to predict the microplastic flow in this system.

The results of the fish analysis will contribute synergistically to a parallel effort financed by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries to develop methods for and quantify microplastics in several important fish species.

During the last year, I co-authored several chapters of the AMAP (Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme) monitoring plan and guidelines on microplastics and litter in the entire Arctic ecosystem.

As a co-supervisor for several PhD students, I am involved in studies on the uptake of microplastics into and influence on plankton, fish and mammals, working together with the department for biological sciences and clinical nutrition in Bergen, and the Nord University in Bodø.

Do you have ongoing master projects?

Together with Ana Lorena Ruano from the Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care, I supervise master student David Messing who is bridging psychology and natural sciences, by reviewing relevant literature for developing a framework for sustainable actions that civil society can undertake to mitigate the impact of microplastics on human health.