Where to find transdisciplinarity, and how to integrate it into education

The modern world is a specialised world, but there is a strong movement to bring together different ways of knowing to better inform societal action on grand challenges, such as global environmental change.

Main content

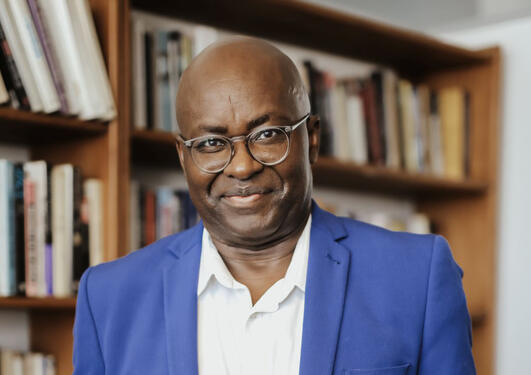

Scott Bremer

Research professor

Centre for the Study of the Sciences and the Humanities, UiB

The modern world is a specialised world, but there is a strong movement to bring together different ways of knowing to better inform societal action on grand challenges, such as global environmental change. This is giving rise to a fertile landscape of approaches for ‘extending science’, including through transdisciplinary research, and we see such approaches taking hold throughout the scientific ecosystem; from academies to funding agencies, universities to policymakers, or enterprise. But while working across knowledge systems may be an everyday routine for some professionals or tradespeople, many academic researchers feel confined to their discipline, and a key concern has been to build researchers’ capacities – skills and literacy – for working in this extended mode. This is seeing a host of under- and post-graduate research and teaching programmes set up to train the future’s transdisciplinary scholars. Yet these programmes can struggle to take root in deeply entrenched academic institutional rules, norms, and cultures that re-produce disciplinary ways of working.

Against this background I want to look at a few places where we can see ‘transdisciplinarity in action’, and which could offer up lessons, realise capacity, and inspire academic researchers. In particular, I argue that all of us as individuals – including scientists – are constantly reckoning across multiple ways of knowing every day, in deciding how to act. By reflexively turning scientists’ gaze inwards, they come to notice the knowledge systems that they creatively combine, reconcile, or compartmentalise and exclude, in a process of what may be called bricolage. For some, these reflections make visible the ways that their life away from the ‘lab bench’ comes to shape their scientific inquiry, and vice versa. I argue that so unlocking individuals’ capacities may be one step to working in a more collaborative way.

Scott Bremer is an interdisciplinary social scientist at the Centre for the Study of the Sciences and the Humanities at the University of Bergen, and at the research institute ‘NORCE Climate’.

His research is on environmental governance, with most recent work on climate adaptation governance. Bremer looks at how science and other ways of knowing are mobilised in support of decisions and action in institutions, including at the so-called 'science-policy interface', with a particular focus on taken-for-granted cultural knowledges and skills; people’s capacity for ‘good timing’ for example. This has seen him working in an extended scientific mode that co-produces research and action on pressing issues with societal groups, guided by perspectives on ‘transdisciplinarity’ and ‘post-normal science’, with active research projects and teams worldwide. It has also resulted in an extensive repertoire of scientific publications on both the theory and practice of transdisciplinary science, and ways to evaluate its impact.

Bremer’s work extends to influencing science-policy and science-for-policy in Europe in his role as Vice-chair of the Young Academy of Europe. In recent years, Bremer has co-designed and organised several under-graduate and postgraduate courses aimed at building young researchers’ capacity for working in a transdisciplinary way.