"Neurodegenerative diseases remain an unsolved mystery"

Professor Charalampos Tzoulis stresses that neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and ALS, represent a global health emergency that can only be tackled through extensive research.

Hovedinnhold

The human brain has fascinated Charalampos Tzoulis since medical school. Tzoulis was born in Greece in 1979. After finishing his medical studies at Albert Szent-Györgyi Medical University, in Szeged, Hungary, he came to Norway, where he specialized in clinical neurology at Haukeland University Hospital and completed his PhD and a postdoctoral fellowship in mitochondrial disease at the University of Bergen. Following this, Tzoulis established his own research group, and became a full Professor of Neurology and Neurodegeneration at Department of Clinical Medicine at the age of 38.

Tzoulis' research focus is to understand the mechanisms underlying Parkinson's disease and develop new therapies. Working toward this goal, he has built and presently lead the Neuromics research group, a specialized multidisciplinary research unit comprising twenty five members and integrating cutting-edge molecular biology, bioinformatics, neuropathology, and clinical research. Furthermore, Tzoulis succeeded in obtaining major strategic funding (€32 million) and establishing Neuro-SysMed, a National Center of Excellence for Clinical Research in Neurological Disease, which he co-directs together with Prof. Kjell-Morten Myhr. In total, Tzoulis has successfully accrued over €40 million in research funds of which more than eight of them are personal research grants.

Why did you choose to dedicate your professional life to studies of the brain?

"Neurodegenerative diseases are currently "the last frontier" in medicine. In comparison, we know a lot more about the processes driving cancer, than we do about neurodegeneration. From a societal perspective, neurodegenerative diseases are a global emergency, which must be addressed within the next 20-50 years. From a scientific perspective, neurodegenerative diseases remain an unsolved mystery, which I find intriguing and highly fascinating", Tzoulis explains.

Parkinson’s disease: The place where clinical trials come to die.

According to Tzoulis, researchers have had surprisingly few breakthroughs in the field of neurodegenerative diseases, despite more than two hundres years of research.

"To date we have no mechanistic understanding of neurodegenerative diseases, nor the means to treat, prevent or delay their development", he says.

Despite the effort: Why do we know so little of the mechanisms behind neurodegenerative diseases?

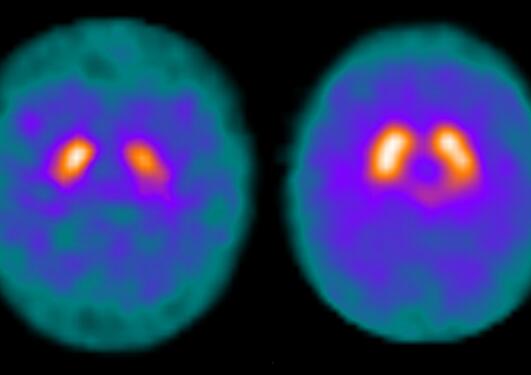

"First of all, the target organ of these diseases, the brain, is not directly available to us for research. In other disease, such as cancer, we are often able to obtain a sample of the affected tissue and analyze it – even test to which drugs it responds best – but we cannot do the same thing with the brain of a living patient. We are limited to either studying the brain indirectly, through imaging such as MRI, or obtaining tissue after death, at autopsy", he says.

Having very limited understanding of the mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases, we are unable to build accurate cell or animal models, which would help us advance our understanding of these diseases and test potential therapies.

He also believes that a part of the problem is the way we define neurodegenerative diseases. He thinks that diseases such as Parkinson's or Alzheimer's, are not one entity, but in fact an entire spectrum of different disorders linked by a common denominator of similar and overlapping symptoms:

"There is increasing evidence suggesting that, for example, the clinical syndrome we term Parkinson's disease is not a single biological entity, but rather a convergent phenotype, resulting from many different biological disease-processes. To understand and treat Parkionson's disease, we need to first discern all the molecular subtypes of disease and develop clinical biomarkers allowing us to identify patients with each disease subtype. We have yet not been able to develop such biomarkers".

He adds:

"There is a saying about Parkinson – or perhaps neurodegenerative diseases in general: "It is the place where clinical trials come to die". We have not been able to identify neuroprotective therapies, able to delay or prevent these diseases, despite hundreds of trials. I believe that one important reason for the consistent failure of trials is that each drug is being tested on clinically selected patient populations, who are heterogeneous in terms of underlying mechanisms and, therefore, also in their response to the treatment being tested. Tragically, it may be that some of the drugs tested actually worked for a subset of patients – but this was never noticed as there was no effect at the group level".

Finding a cure by targeting mitochondrial and discerning the different types of Parkinson's

"One of my flagship-projects is to stratify Parkinson's disease according to underlying mechanisms, and apply tailored therapies", Tzoulis explains.

Together with his team, they are well underway in this effort. Tzoulis' work has greatly advanced the knowledge of how mitochondria, the cells' power-generators, are involved in Parkinson's disease, and provided evidence that they may, indeed, hold the key to therapy. Inspired by these findings, Tzoulis started clinical trials of compounds promoting mitochondrial function. The research group has just completed an early (phase I) trial showing that the treatment is safe, reaches the brain and influences its metabolism. Encouraged by these findings, they are now conducting the NO-PARK trial, a large (phase II) trial with 400 patients, aiming to determine whether this therapy can delay the progression of Parkinson’s disease. (Information regarding these trials can be found on clinicaltrials.org: NCT03816020, NCT03568968).

In their latest work, Tzoulis' team has discovered evidence suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction may, in fact, define a distinct biological subtype of Parkinson’s disease. He is currently applying for an ERC Grant to explore this intriguing possibility.

"If successful, this project has the potential to revolutionise our understanding of Parkinson's disease, moving the research frontier beyond the constraints of arbitrary clinical definitions, into an era of objective, biologically-defined disease subtypes – each with distinct, knowable pathogenic mechanisms, susceptible to stratification and, potentially, targeted therapy", Tzoulis explains.

Solving neurodegeneration will require decision-makers to allocate budgets rivaling those spent on the global petroleum industry or space-exploration programs.

"We are facing a global social and health emergency".

He believes the same approach can be used to learn more about other "black boxed" neurological diseases:

"If we can prove the concept that Parkinson's is an array of different diseases – and thereby understand and treat it, the same principle will likely be applicable to other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer and ALS", says Tzoulis.

He admits it will require a huge effort, and a willingness to prioritize research on this matter:

"It will require research, a lot of research. Neurogenerative diseases are complex, and we need to study large groups of patients. It will be extremely expensive, but not unfeasible. Solving neurodegeneration will require decision-makers to allocate budgets rivaling those spent on the global petroleum industry or space-exploration programs. I believe we have an obligation to allocate more fund to neurodegeneration research if we wish to avert the coming global crisis".

If the society fails to prioritize it, he believes that cost will be even larger:

"We live longer. Medicine has been successful in treating other types of disease, such as cardiovascular disease and many forms of cancer. Globally, there are about 10 million living with Parkinson's, 80-100 million people with dementia today. These numbers are expected to double in the next twenty years. In addition to the immense impact these diseases have on the lives of patients and their families, they also cause a huge social and economic burden. We are facing a global social and health emergency and need to tackle this at the same level as other major problems, such as climate change", he says.

"Curing dementia is science fiction"

Despite all this, he remains positive:

"I hope that in five years, we will have stratified these diseases in subtypes, and reached a better understanding of their mechanisms. In ten years, I hope we can have drugs on the market, that are able to delay or prevent the development of the different subtypes of the diseases. In 20 years, I hope we will have transformed neurodegenerative diseases - from being a death sentence for which nothing can be done, to a chronic but treatable illness, which patients and their families can live with, while maintaining their dignity and quality of life", he says:

What about the prospect of curing these diseases, such as dementia?

"These diseases are inherently linked to aging. I believe that delaying and postponing the development of the diseases is within our abilities for the next 20 years. Curing them altogether, would mean nullifying aging itself. From a scientific view this is currently more in the realm of science fiction. Exciting science fiction, but still many decades if not centuries into the future", Tzoulis states.