Medieval Manuscript Facsimiles: Celebrating the Munkeliv Psalter

To celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of the Czechoslovakian donation of a facsimile of the Munkeliv Psalter to Norway, the Special Collections of the University of Bergen Library sponsored two events during Medieval Week 2023. Åslaug Ommundsen, professor of Medieval Latin at University of Bergen, held a lecture on this notable piece of cultural heritage from medieval Bergen (Det birgittinske Munkelivspsalteret: Eit handskrift frå mellomalderens Bergen). Thereafter, a panel led by Senior Academic Librarian and Scientific Manager of the Manuscripts and Rare Books Collection at the University of Bergen Library, Alexandros Tsakos, looked at facsimiles, their historical development, and their use in teaching and research. A synopsis of the panel is presented here.

Hovedinnhold

On 8 September, Alexandra Bolintineanu (University of Toronto), Aidan Conti (University of Bergen), Sonja Drimmer (University of Masschussets, Amherst), Julia King (Lambeth Palace Library), and Giovanni Scorcioni (Facsimile Finder) met at the University Library. The discussion opened with a presentation of the Munkeliv psalter facsimile and continued with the role of facsimiles in preserving and promoting cultural heritage, their importance in teaching and in research.

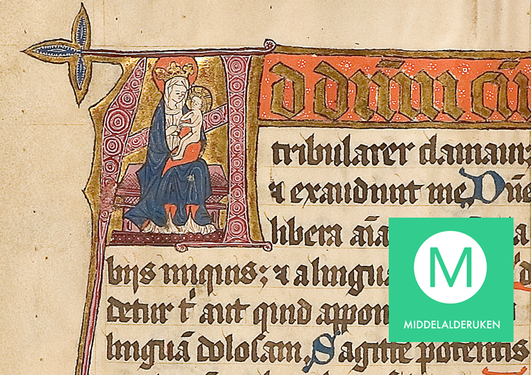

The Munkeliv psalter, as Julia King related to the audience, was written in the middle of the 15th century at the Birgittine monestery of Munkeliv on the Nordnes peninsula in Bergen. This beautiful book has long been recognized for its importance to the history of written and visual culture in medieval Norway and women’s role in this culture. Founded in 1120, Munkeliv was initially a Benedictine monastery before it became a Birgittine monastery in 1427, the period in which the psalter was written. As Julia explained, Birgittine monasteries are particularly interesting for female religious culture. Their rule required them to live an enclosed life with no possessions, but they were allowed to have as many books as they wished for personal study and devotion.

The Munkeliv Psalter is one of the few codices still extant from medieval Norway, and one of five extant psalters with a Norwegian medieval provenance. Remarkably, the scribe and artist, Birgitta Sigfusdotter, identifies herself on fol. 173 of the book:

Ego Brigitta filia sighfusi Soror conventualis in monasterio munkalijff prope bergis scripsi hunc psalterium cum literis capitalis licet minus bene duam debui. Orate pro me peccatrice.

I, Birgitta Sigfus’s daughter, nun in the monastery Munkeliv at Bergen wrote this psalter with initials, although not as well as I ought. Pray for me, a sinner.

Earlier in the day, Åslaug Ommundsen explained how this work may have journeyed from Munkeliv to Prague. When the Birgittines left Bergen in 1531 and moved to Vadstena, the Munkeliv psalter may have come with them. On a flyleaf in the book, one finds the name of Jacobus Typotius (d. 1602), a Flemish humanist employed by the Swedish king. In the 1590s, Typotius travelled from Sweden to Prague and died there a few years thereafter. He may have had the psalter with him. Its route thereafter to the Metropolitan chapter library remains uncertain.

The facsimile of the Munkeliv Psalter was produced in 1963 by the Photographic Department of the State Library of Czechoslovakia so that the Czechoslovakian government could present the object to the government of Norway in Oslo. It was subsequently transferred to Bergen, the city where the Psalter was originally produced. Today, it is kept in the Special Collections of the University of Bergen Library together with related material (such as the letter of transfer from Oslo to Bergen) that attest to its importance of cultural exchange. The facsimile, as Julia King related, bears hallmarks of facsimile production in the period. The facsimile spans three volumes (rather than the original’s single volume) and comprises black and white photographs, each tipped into an individual binding station. The present book is made to look ‘medieval-ish’: the boards are covered in white, parchment-like paper; the lettering of the front board imitates a gothic hand; the boards have ‘yapp edges’ that extend out over the text block.

The role of facsimiles in promoting the cultural heritage of a community, facilitating access to the original’s content and form, while at the same time protecting the originals, was taken up by Aidan Conti who spoke on facsimile edition projects of the early to late twentieth century, such as Codices Latini Antiquiores (1929-1992), Manuscrits datés (1953--), Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile (1951--), and Early Icelandic Manuscripts in Facsimile (1958--).

Sonja Drimmer followed with a discussion of one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable facsimiles. The Rupertsburg manuscript of Hildegard’s Scivias was prepared under her supervision in the 1100s. Between 1927 and 1933, the nuns of the Hildegard abbey in Eibingen produced a detailed facsimile by hand, which relied both on examination of the original twelfth-century manuscript and consultation of photographs made earlier in the 1920s. The manuscript itself, sent to Dresden for safe keeping during the Second World War, was lost. As a result, many of the vivid and beautiful color images circulating today of Hildgard’s Scivias are sourced from the reproduction by the nuns.

Expanding on the role of photographic reproductions of medieval manuscripts, Alexandra Bolintineanu suggested the ways in which digital facsimiles can be used in present-day teaching. Working in the field of Old English, Alexandra focused on a manuscript containing works of the Anglo-Saxon monk, abbot and priest, Ælfric of Eynsham found in a manuscript from Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and available to all via the Parker Library On the Web project.

Of course, academic use of facsimiles represents an important generator, but, as Julia King suggested, bibliomania also serves as a motivator for the production of facsimiles. Julia cited an example of engraved reproductions of medieval books in the 18th century, a process that both presented aspects of the original as well as produced a beautiful book in itself.

Indeed, the interest and consequent demand for such objects was elaborated by Giovanni Scorcioni, who is the founder and owner of Facsimile Finder. Starting as an independent supplier of facsimiles to librarians and private collectors, Facsimile Finder has since become more involved in the process or producing facsimiles as well. As a result, Giovanni has been a consultant to many facsimile projects, including: the Psalter of Blanche de Castile (published in 2021 by Mueller & Schindler); twelve of da Vinci’s sketchbooks (with Faksimile Verlag); and a forthcoming project, a high-quality facsimile edition of the Vercelli Book, an Old English manuscript that made its way to Vercelli in the early Middle Ages.

Giovanni also provided elucidating insights into the facsimile market. Seeing the market as taking shape in the 1960s and 1970s primarily in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, Giovanni stated that initially about 90% of sales were to libraries and the remaining to private collectors and individuals. Today, less than 1-2% of sales go to libraries; private collectors and interested parties make up the preponderance of sales.

Giovanni outlined the five steps in producing a facsimile: choice and planning; photography; digital editing; printing; and binding. He explained that each involves various professionals and differing expertise, as well as advanced technologies and expensive materials. For these reasons, the production cost of a facsimile is high, which is reflected in the final price. As such the physical facsimile, a luxury item in its own right, does not necessarily obviate the value of digital facsimiles; both help different audiences understand the original.

Overall, this discussion highlighted differences between digital and physical facsimiles within contemporary interest in the materiality of the book, both in the Middle Ages and today. Facsimiles in their various forms promise to facilitate access to material to which access may often be limited for reasons of preservation.

In this regard, the Munkeliv psalter, medieval Norway’s most beautiful book, provides an excellent demonstration. The facsimile presently held in the Special Collections of the University of Bergen Library now represents an artefact of Cold War Europe itself. Interesting as the present book is, the technical limitations of the age in which it was produced inhibit certain areas of inquiry into this book (most obvious of which may be the coloring of the original manuscript, lost in the black-and-white facsimile). In marking the sixtieth anniversary of the presentation of these volumes to Norway, we hope to also set in motion the process for developing a digital facsimile so that both professionals and amateurs are able to view this magnificent testament to women’s writing in medieval Bergen.