Faster growth of the placenta is linked to increased risk of preeclampsia

Research sheds light on how genetics influences the growth of the placenta and reveals a link to increased risk of disease in the mother.

Main content

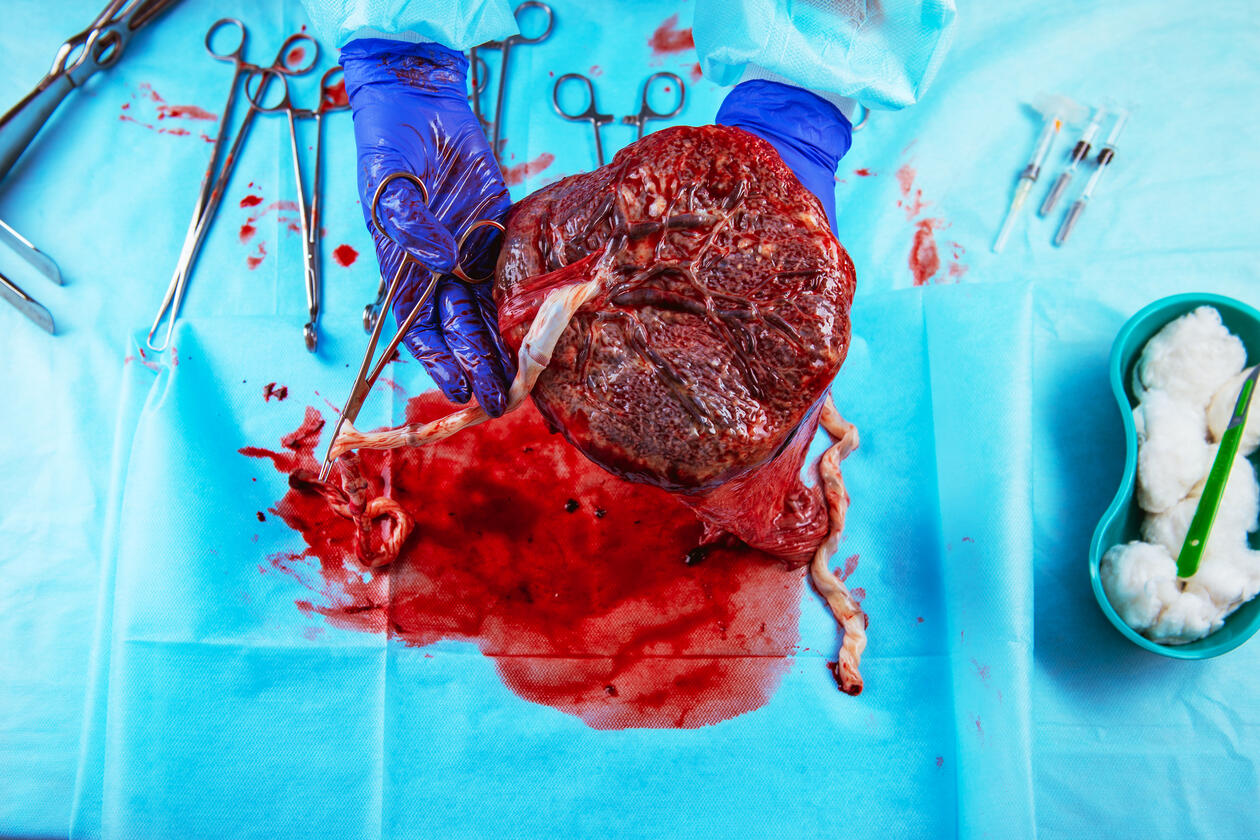

The placenta is an organ which grows in the womb alongside the foetus, which is attached to it by the umbilical cord. It is the only organ that contain tissue from both mother and child. The placenta provides oxygen and nutrients to the growing foetus and removes waste as the baby develops. A poorly functioning placenta is associated with pregnancy complications, and later risk of disease in the child.

Despite its key role, little is yet known about how the growth of the placenta is regulated.

"Understanding placental growth is important, as babies with very small or large placentas are at higher risk of complications", Professor Pål Rasmus Njølstad at the Department of Clinical Science, explains.

He and his colleagues at the University of Bergen, together with colleagues in UK and Denmark to has led a largescale international collaboration to examine placental growth in the greatest detail yet.

Together they carried out the first ever genome-wide association study of the weight of the placenta at birth, generating several revelations.

"Among the findings published in Nature Genetics, we concluded that faster growth of the placenta can contribute to risk of preeclampsia, and to earlier delivery of the baby", says Njølstad.

A fast-growing placenta may upset the balance.

The placenta is an important organ during pregnancy, providing an intricate and vital link between mother and baby.

"In our study we have identified 40 variations in the genetic code linked to how big a placenta can grow, which improves our understanding of this vital organ in humans. Several of these genetic variations also influence the weight of the baby, but many are to be predominantly concerned with placental growth", Njølstad explains.

The team found that where the genetic code of the foetus meant it was more likely that the placenta would grow bigger, there was a higher risk of pre-eclampsia in the mother.

"This could be because the placenta grows too fast, which can upset the balance between the baby’s demand for resources and how much the mother is able to provide, which can be a factor in pre-eclampsia that occurs late in pregnancy", says Njølstad.

Placenta growth is linked to pregnancy length.

Pre-eclampsia is a condition that may develop in pregnancy, which causes high blood pressure. Some of the mother’s organs, such as the kidneys and liver, stop working properly.

Detecting it early is essential to avoid severe health problems for mother and baby, yet how preeclampsia develops isn’t fully understood.

"Our study suggests that faster growth of the placenta contributes to a higher risk of preeclampsia in the mother. It seems specific to placenta growth because we did not find the same risk when we looked at the genetics of baby weight", says Professor Rachel Freathy at the University of Exeter Medical School, and a co-lead of the paper.

Faster-growing placenta was also linked to shorter pregnancy.

"We found that babies with genetic code for a bigger placenta were more likely to be born earlier, which underscores the importance of investigating placental biology in studies of pregnancy duration and the timing of delivery", says another of the co-leader of the study, senior researcher and group leader, Bjarke Feenstra at the Copenhagen University Hospital and Statens Serum Institut, Denmark.

Insulin was related to placenta growth.

One key finding from the study related to insulin, a hormone that regulates blood sugar. The foetus produces insulin in response to glucose (sugar) from the mother, which acts as a growth factor.

The team found this insulin is also linked to the growth of the placenta, which helps to explain why placentas tend to be large in pregnancies where the mother has high blood glucose due to diabetes.

Further studies are needed.

"Our work is just the starting point for future research which could help us understand far more about the placenta’s role in the growth of the baby and risk of pregnancy complications", says Professor Stefan Johansson, also co-lead at the University of Bergen.

He thinks this is a great first step, but that the final weight of a placenta can only tell us a limited amount about its function:

"Further studies are needed to examine the shape and development of placenta over the course of pregnancy", he underlines.

Read the article here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41588-023-01520-w

This article is also published in Science Norway.