Completed projects

List of archaeological field projects successfully completed by researchers affiliated with the Norwegian Institute at Athens.

Main content

- NORWEGIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY IN THE KARYSTIA (NASK)

- NORWEGIAN ARCADIA SURVEY - PART III (NAS 3)

- SOUTHERN NAXOS GREEK-NORWEGIAN UNDERWATER SURVEY

- IRAKLEIA CAVES EXCAVATION PROJECT (ICEP)

- GREEK NORWEGIAN DEEP WATER ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY AT ITHACA

- NORWEGIAN ARCADIA SURVEY - PART II (NAS 2)

- HELLENIC-NORWEGIAN EXCAVATIONS AT TEGEA (HENET)

- FIELDWORK AT PETROPIGI (KAVALA)

- NORWEGIAN ARCADIA SURVEY (NAS) - 1998-2001

- INVESTIGATIONS IN THE TEMPLE AND SANCTUARY OF ATHENA ALEA (1991-1994, 2004)

NORWEGIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY IN THE KARYSTIA (NASK)

- A program or research consisting of an archaeological diachronic surface survey of theKatsaronio Plain, located north-west of the town of Karystos. The project lasted from 2012 to 2016 and is in the study and publication phase as of 2017.The Norwegian Archaeological Survey in the Karystia was a five-year long project of systematic archaeological investigation in the Karystia, which is the part of southern Euboea centered on the modern town of Karystos. The long-term goal of the project was to record and reconstruct the cultural landscapes in the Karystia and the ways the landscape was constructed, lived in, and used by people inhabiting the Karystia in the past, from the prehistoric times to the present. The Katsaronio plain was hitherto virtually unknown in archaeological terms, since very little research has been done there in the past. The primary objectives of the project were to explore the long-term connection between people and the landscape they inhabit and to gather evidence that reflects the past (particularly prehistoric) sociopolitical organization of Karystian communities and their access to and management of agricultural resources. Additionally, the project included the search for evidence for the earliest known (Late Neolithic) settlement of the area and it also functioned as an informal field school where students of archaeology and classics from Norway and elsewhere can obtain field experience. More than 100 students, volunteers, and professional archaeologists from Norway and more than a dozen other countries have taken part in this project.

- NASK was organized as an intensive diachronic pedestrian surface survey. The entire target area of approximately 20 square kilometers was surveyed by team members spaced ten meters apart, assuring maximum coverage and accuracy. Concentrations of archaeological materials (termed findspots), features (immovable objects such as walls, pits, wells), significant natural resources (e.g., springs), and individual finds of any kind (e.g., pottery, chipped and polished stone, metals, etc.) were recorded using a GPS device and their location and other information associated with them (i.e., their context) is entered into a database, which was analyzed using GIS software. Special attention is given to findspots, as likely surface indications of buried archaeological sites; all findspots were surveyed in greater detail for evidence of differential spatial distribution of certain kinds of artifacts and/or features. The project introduced the use of Android-based tablets to the survey to excellent results in terms of speed and recording accuracy.

- The project managed to discover and record 99 new archaeological sites in the 20 sq km survey area. The sites range in date from the Final Neolithic to Ottoman and in size from a handful of sherds and lithics to massive concentrations of archaeological artifacts and features spread over several hectares. The project also discovered sites that will likely be explored in the future through archaeological excavation (e.g. Gourimadi prehistoric site).

For some images from the project, please visit its Facebook page. For any questions, please contact the project’s director, Dr. Zarko Tankosic.

***

NORWEGIAN ARCADIA SURVEY - PART III

- The Norwegian Arcadia Survey III (NAS III) is the third survey project in the area of ancient Tegea, Arcadia under the aegis of the Norwegian Institute at Athens. The survey is directed by Mari Malmer (University of Gothenburg) and is conducted as a two-season project by an international team of researchers (2016-2017).

- NAS III will investigate new areas and employ new methods in an effort to better understand the pre-urban landscape around Tegea and its relationship with the sanctuary of Athena Alea during its early period, ca. 950-500 B.C. Little is known about the inhabitants of Tegea in this early period beyond the evidence from the sanctuaries; the Geometric period is essentially unknown outside the cultic context. The thriving cult of Athena Alea and the construction of other sanctuaries from the Geometric and early Archaic periods are testaments of early activity in the area, but the appearance of the urban centre rather suddenly around 550-500 B.C. is the first sign of a real settlement. Where and how did the Tegeans live? The gradual elaboration of the sanctuary culminating in the construction of the monumental temple ca. 600 B.C speaks of a degree of organisation that seems incompatible with a population predominantly engaged in mobile pastoralism - yet this occurs at least half a century before any real traces of habitation appears.

- Areas not thoroughly investigated will now be covered by means of a detailed form of field survey and pXRF (portable X-Ray Fluorescence) will be utilized for scientific ceramic studies in a diachronic and synchronic perspective. Parallel to the investigation of pre-urban settlements NAS III will conduct a geophysical survey with GPR (Ground Penetrating Radar), 2D-resistivity imaging and core drillings. The survey project aims to bridge the gap between the sanctuary and its surroundings through a comparison of the material found in the field with that of the sanctuary, and through a geophysical investigation of the landscape.

- NAS III aims to contribute to a better understanding of the ancient landscape in both human and geological terms. Documenting human activity in the pre-urban phase will provide an opportunity to understand the dynamics behind the early polis, from scattered hamlets to an urban core. Tegea is in many ways a unique case, as the polis in political terms (marked by the construction of the monumental temple) and the polis in physical terms (marked by the construction of the urban, planned centre) takes places in two distinct phases. In other poleis the process was more gradual and therefore difficult to study. This makes Tegea an ideal case for investigating the rise of the polis.

- In 2016, the NAS III team successfully located and documented a small, pre-urban site in an area called Metousia just south of Alea. The site appears to have had continuous occupation from the second half of the 8th century B.C. to the time of the construction of the urban centre and beyond, lending support to project hypotheses.

***

SOUTHERN NAXOS GREEK-NORWEGIAN UNDERWATER SURVEY

- The underwater survey of the South coast of Naxos is a three-year long joint research project of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities in Athens and the Norwegian Maritime Museum in Oslo in cooperation with The Naxos Diving Centre. The project is administered by the Norwegian Institute at Athens. Its objective is the survey of harbours and wreck sites from the Classical to the Byzantine period along the South coast of Naxos.

- The project will give unique insight in how remote areas without obvious large coastal settlements were connected to the sea and thereby the Mediterranean world. It might give new knowledge on unknown coastal nuclei, which served as a link between the inland settlements and the sea. It shall further be examined if ideal natural harbours were only used in connection to existing settlements during a certain span of time or if they are unaffected by changes in the settlement patterns on land.

- The sparsely populated south coast of Naxos is in many ways ideal for a survey of harbours. Its natural harbours are not included in larger settlements and are potentially well preserved, even though the increase in tourism related boat trips to the bays and the building of smaller harbour constructions already have affected some of the ancient sites. In contrary to other landscapes where ancient and medieval harbours are largely destroyed or incorporated into new harbours (compare Chora), it must be assumed that the South coast has its’ original harbours largely preserved and can give a unique insight into the maritime infrastructure and trade in these periods.

- The project aims to map all harbours along the South coast between Panermos and Aliko and to establish knowledge of their specific function and their periods of use. There are only very few settlements known from the Greek to the Byzantine period in that area. Most important is Kastro Apalirou currently the focus of the ongoing Norwegian Naxos Survey. Kastro Apalirou is a 7th or 8th century settlement, which gained importance during the Byzantine period. Another nucleus for surrounding farmsteads was certainly the fortified farm Pyrgos Chimarou, which maintained its’ importance for the area also in the Byzantine period, when it served as a monastery. Thirdly, a Late Roman castle and a Bronze Age settlement at Panermos indicate periods of activity around the natural harbour.

- The project carries out an extensive search of the seabed with Side-Scan Sonar and visually with free diving and SCUBA diving. The main mode of detail measurement is 3D photogrammetry. Sites identified are being documented, searched with metal-detectors and ceramics sampled. A selection of sites will be subject to small-scale excavations in the coming seasons. Two extensive harbours or anchorages have already been surveyed. One of these harbours, Panermos, is characterized by many ballast piles, which prove that ships not only unloaded but also loaded cargo in the harbour. Rich finds of broken ceramics on the seabed accounts for loading and unloading activity at least during the Roman Imperial and Late Roman periods. Wreckage of several ship wrecks have been located on reefs along the south coast and can shed light on the inventory of ships sailing along the coast in the first millennium AD. The other site is located within a days’ journey by foot from Kastro Apalirou and might have served as an anchorage for the settlement. The chronology of the ceramics is still being evaluated, but some finds indicate the harbour was used both before the settlement but also during its peak in the Byzantine period.

- After the first publication of research results at the Israeli newspaper Haaretz 18. desember 2017: Cluster of Roman Shipwrecks Suddenly Noticed Off Greek Island of Naxos many other international news outlets have also picked up the story: Newsweek, Daily Mail, Atlas Obscura , Greek Reporter, EXPRESS Sputnik International

***

IRAKLEIA CAVES EXCAVATION PROJECT (ICEP)

- The program of archaeological excavation and survey of caves on the island of Irakleia in the Lesser Cyclades that took place between 2014-2016. The project was a cooperation—synergasia—with the Ephorate of Palaeoanthropology and Speleology of Greece and it was directed by Drs. Fanis Mavridis from the Ephorate and Zarko Tankosic from NorwInst. The project was funded by the Norwegian Institute and by a generous independent grant from the Swiss Federal Office of Culture.

- Irakleia is a small island, part of the Lesser Cyclades, located south from the island of Naxos. The project on this island consisted of a systematic excavation of the Agios Ioannis/Cyclops cave complex on the island known to have been inhabited from early prehistoric times. The project aimed to recover evidence for the diachronic use of the island's caves, especially in the light of prehistoric Aegean maritime interactions.

- Our combined teams opened several test trenches in four caves and excavated them to the depth of more than 1.5 m. The evidence collected shows that the caves have been in more or less continuous use from at least the Early Bronze Age until the modern times. We have also confirmed that one of the caves contain large deposits of tephra from the Bronze Age Santorini volcano eruption, making this site extremely valuable for establishing Aegean Bronze Age chronology and for geologist and geoarchaeologists studying this event that may have led to important social changes and the end of the Minoan dominance in the Aegean.The preliminary results of our investigations were presented at the conference on Cycladic archaeology that took place in May 2016 on the island of Syros. As of 2017, the project is in the study and publication phase. Images from the project can be seen at its Facebook page. For any questions, please contact the project co-director Dr. Zarko Tankosic.

***

GREEK NORWEGIAN DEEP WATER ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY AT ITHACA

- Hi-tech investigation of seabottom around Ithaki (Ionian Islands)

- Greek-Norwegian co-production

- Directors: Ms Katerina Delaporta (Department of Underwater Antiquities), Dr Marek E. Jasinski (Norwegian University of Science and Technology at Trondheim)

- Financing from the Greek Ministry of Culture, Telenor Hellas S.A., Sarantitis & Partners

- Pre-season 1999, regular seasons 2000, 2002-2003

- The "Greek-Norwegian Deep-Water Archaeological Survey" is a joint undertaking by the Greek Department of Underwater Antiquities (EEA), the Norwegian University of Science and Technology at Trondheim (NTNU) and the Norwegian Institute at Athens (NIA). Its main goal is to survey the seabed in selected areas in Greece using advanced underwater technology, and thereby create a database of submerged archaeological sites as an aid to their protection. The project is directed by Ms Katerina Delaporta (EEA) and Dr Marek E. Jasinski (NTNU), the Greek team and the research vessel financed by the Greek Ministry of Culture, the Norwegian side by the generous sponsorship of Telenor Hellas S.A. and Sarantitis & Partners.

- The co-operation was initiated in September 1999 when a one-week pre-season was conducted in the Northern Sporades. The purpose was to familiarize the Norwegian team with local conditions, both above and below the water surface. A number of known wreck sites were visited with the NTNU side-scan sonar, a torpedo-like instrument towed by the research ship, which sends a continuous image of the sea-bottom to the onboard computer. The technicians learned to distinguish the digital imprint of the amphora mounds of wrecked merchantmen from natural rock formations and outcrops which create similar representations. In the process four potential new wrecksites were identified, of which one was confirmed by EEA divers and dated to the Byzantine period.

- In June 2000 the research area was moved to Ithaki for the first full season. During two weeks the team gathered digital data around Ithaki and in the sound between Ithaki and Kefallonia. Despite the very anomalous seabed, characterized by a rapid drop to depths beyond 100m and a rocky terrain, which caused some difficulties (a wreck may be confused with rocks when it lies among them and/or when the sonar passes over the site on a course at an angle to the dominant lines of the underwater topography), the work with the sonar resulted in a comprehensive coverage of the north-eastern coast of Ithaki. Close to one hundred targets were catalogued, of which a selection was made for verification. Employing the Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) of the Sperre A.S. company from Norway allowed the team to eliminate a number of possible targets as being elements of the seabed.

- Two new wrecks were extensively documented using the ROV. This involved collecting video footage for the study and dating of the amphorae (at first contact they appear to be Late Republic/Early Roman Empire in date), and creating a photo mosaic with a digital camera. The one wreck, reported by Fiskardo's Nautical and Environmental Club (Kefallonia), has been extensively damaged by sportsdivers. The other consists of a complete amphora cargo at a protective depth. This spectacular find resulted from an intensive search in an area indicated by a fisherman who had pulled up an amphora in his nets. It illustrated in a convincing manner the abilities of the team to use both sonar information and the Project’s complementary approach of interviews with fishermen to obtain the best possible results. A third wreck consisting of roof tiles was only partially documented since a greater number of tiles had been signaled than were found by the ROV. Further work in the area is necessary in 2002 on a cargo of lead bars so a return to the site is planned.

- The "Greek-Norwegian Deep-Water Archaeological Survey" combines the extensive knowledge of the Greek waters of the EEA personnel with hi-tech survey equipment owned and operated by the NTNU or developed by Sperre A.S. While side-scan sonars have been used previously in Greece, the combination of the sonar for covering large areas and the ROV for rapid verification is a new approach which does not resort to vastly more expensive research submarines.

***

NORWEGIAN ARCADIA SURVEY - PART II

Norwegian Arcadia Survey. Part II. Sites and Marginal LandscapesReport for the archaeological fieldwork conducted in 2011

- The Norwegian Arcadia Survey Part II (NAS 2) conducted archaeological fieldwork in three periods during 2011. The most extensive fieldwork was conducted in the period 10.06 – 24.06.2011. The participants were then Hege Agathe Bakke-Alisøy (the project manager), Nils Ole Sundet, Jonatan Krzywinski, Dorthea Alisøy and Harald Klempe. Our work was this year funded by the Norwegian Institute at Athens, the Meltzer foundation and the B.E. Bendixens fund. In addition one week of find processing was done in February and one in November, then only by the project manager, Hege Agathe Bakke-Alisøy.

Aim

- Our aim for this year’s activity was to get a better understanding of the finds in the area of Ag. Dimitrios and Mirmingofolies. During the field season of 2010 a short reconnaissance was done resulting in both prehistoric and medieval finds. This year the geologist Harald Klempe conducted investigations using a ground penetrating radar (GPR) of a find concentration previously found during the season of 2009 at the site of Chairolimnes (site 1). This archaeological material here mainly prehistoric, and then Early and/or Middle Helladic. We have chosen this site due to its very marked find concentration. We thus consider it to be suitable for testing the method of GPR searching for prehistoric structures.

- Also this year a great amount of archaeological material previously collected was analysed. We aimed to complete processing the material collected during the fieldwork in 2008 and 2009.

Results

- In February the project manager, Hege Agathe Bakke-Alisøy, stayed one week in Tegea analysing the archaeological material found during the fieldwork in 2008 and 2009. The Swedish archaeologist Ann-Louise Schallin was of great help as she stayed for one day. She is an expert on Mycenaean pottery and has previously worked with the prehistoric material from the Asea survey. Her input was vital for getting a more detailed chronological understanding of the material.

- The processing of the archaeological finds was continued during the season in June. The focus was on the prehistoric material, but also parts of the medieval and early modern material was analysed. We did not manage to complete the work, but some preliminary tendencies are emerging. At the site Chairolimnes (site 1) are there at least two concentrations of finds both dated to the Early Helladic. This correlates with the chronological interpretation by Roger Howell, but only one of the find concentrations is included in his study. Despite chronological similarities the two find concentrations show marked differences in type of archaeological material present. This may represent two different settlements, not contemporary, or two distinct activity areas within the same settlement. A further analysis of the material is needed. At Chairolimnes there are also traces of later settlements from medieval and early modern period. This material has yet not been studied. One of he find concentrations of Early Helladic find was chosen as a test area for using GPR. This investigation was conducted by the geologist Dr Harald Klempe, University College Telemark. The results from this investigation are not ready at this point, but the preliminary results are promising. There are clearly structures underlying this find concentration, but a further analysis is needed to try to relate the finds with the possible structure.

- Early Helladic material is also found at the site Mirmingofolies (site 5). It should be said that this is based on a very limited archaeological material. Roger Howell reports of this site and also dates it to Early Helladic. He also refers to graves previously found be local farmers. At this location there are some small stone structures. Their location as well as the stones used indicates that this could be grave mounds. The survey conducted this year also revealed new stone structures nearby. The majority of these are of a medieval or early modern date, probably related to the settlement at Ag Dimitrios (site 6). Most of these structures are agricultural terrace walls and irrigation canals. However, there are a few low mounds that clearly precede these later structures. A further investigation of this area is thus needed.Following the dirt road down from Mirmingofolies towards Ag Dimitrios we found a marked concentration of finds. Some of these clearly date to Late Helladic, and most likely also Late Helladic III. The concentration was discovered last year, but a systematic survey, using method 4 (a survey-transect along a dirt road. A transect is 100 meters long and as wide as the road. One field walker in each wheel track and finds are counted for each 20 meters. One sample of the archaeological material is collected for the whole transect. This should be a representative sample according to type and chronology), was conducted this summer. A full investigation of the area is, however, difficult due to very dense vegetation. So far this is the only site with a Mycenaean dating within our survey area.

- The site Psili Vrisi Vationa (site 3) is by Roger Howell interpreted as a Mycenaean site. The survey material collected during the field season in 2009 indicates, however, to a Middle Helladic and early part of Late Helladic (LH I) dating. Initially we had also hope to conduct investigations with GPR at selected areas of this site. Unfortunately, we ran out of time. Hopefully a GPR investigation can be done next year at Psili Vrisi Vationa.

- The filed survey that was conducted this year was in the area of Ag Dimitrios and Mirmingofolies. This was a continuation of the work done previously year. As already mentioned we registered an area just south of Mirmingofolies (site 4) with various stone structures. The majority most likely related to the medieval and/or early modern settlement of Ag Dimitrios (site 5). This area was surveyed using method 5 (transects of irregular shape and size. This method is applied for reconnaissance in new areas. The number of filed walkers may vary. One representative sample is collected for each transect). We also tried to map some of the stone structures in order to get an impression of their extension and character. Starting at Mirmingofolies (site 4) we applied method 4. This method of survey was done down to Ag Dimitrios. Beside the concentration of Mycenaean finds medieval and early modern finds were scattered all over, but increasing towards the site of Ag Dimitrios (site 5). A reconnaissance (method 5) was done covering most of the hill of Ag Dimitrios. On the western slope of the hill, next to a dirt road leading down to the modern village Psili Vrisi, there was a spring with a large cistern. This slope was very fertile and covered by very high terrace. On the western top of the hill several stone structures, possibly related to a settlement, were found. All the finds from this area are consistent with the preliminary dating to medieval and/or early modern period. Very dense vegetation is also a problem in this area, especially in the western slope.

Conclusions

- This year’s fieldwork has been very rewarding giving interesting results. The continuing analysis of mostly the prehistoric material has resulted in a better and more detailed chronology. The archaeological field work conducted has resulted in one new settlement with Mycenaean pottery as well as a better understanding of the extent of the medieval/early modern settlement at Ag Dimitrios. At the early Helladic settlement at Mirmingofolies, also documented by Howell, we have found some possible grave mounds.

- In the area of Chairolimnes we have also conducted an investigation using GPR. The preliminary results are so far promising, but further analysis is needed. Hopefully we can relate these finds with the concentration of Early Helladic finds in this area.

Publications

Bakke et al, ”Tegea: Norsk arkeologi i Hellas. En innledning”, Viking. Norsk arkeologisk årbok, 2010, nr. 73, s. 173-178.Bakke, J., ”Finnes det et bysantinsk Tegea: Problemer og hypoteser i den peloponnesiske middelalderarkeologien”, Viking. Norsk arkeologisk årbok, 2010, nr. 73, s. 205-220.>Bakke, J., ”Den greske bystatens geohistoriske marginer: Om videreføringen av norsk landskapsarkeologi i Tegea 2008-2012”, Klassisk forum, 2010, s. 47-60.

***

Hellenic-Norwegian Excavations at Tegea

The 2010 excavation team

By Linn Trude Lieng, IAKH, University of Oslo(Archaeological remarks are based on Knut Ødegard’s report from the excavations of 2010)

- In the course of four weeks from the 14th of June 2010 to the 10th of July 2010 the Norwegian Institute at Athens, in collaboration with the 39th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities and the 25th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities carried out a third campaign of excavations at the ancient site of Tegea.

- The excavation team consisted of a Greek, Norwegian, Italian and Danish crew made up of students and researchers from the Peloponnesian University, Greece, the University of Oslo, Norway and the University of Aarhus, Denmark.

- Prior to the excavation two trenches opened in the 2009 season were extended by surface stripping the area in between and widening the investigation area to 15 x 40 meters. This gave the team the opportunity of clarifying some of the questions that remained from the 2009 excavations. Within the area investigated during the course of the excavations four specific areas of interest emerged.

Post-Byzantine floods

- The most recent documented activity at the site was a flood channel that flowed in a south to north direction across the site, most probably during periods of high rainfall and floods. The plain is still today very wet during winter, and the team noted that flooding had in the past seriously disturbed the stratigraphy of the site.

- The flood channel was clearly visible as a band of dark greyish deposits running northwards from square D15 to D12 (see fig.1).

- During excavation it became clear that the layer deepened towards the north of the excavation area. A trench was dug through the channel in square D12, and despite having removed more than one meter of deposits the bottom was not reached by the end of the season. The stream fill consisted of silt, mixed with pottery and tile fragments as well as stones, probably redeposited from the house structures in square D15.

- So far we have no indication on the date of the stream, but a post-Byzantine date is the most probable as the stream’s action had over time demolished part of a late Byzantine wall.

Byzantine house structures and a road

- During the 2010 season a number of Byzantine wall bases were uncovered: They were simple, narrow and made of roughly hewn stones of uneven size, and have been interpreted as foundations for mud-brick-walls. None of the walls have so far been securely dated, but finds connected to the walls in square D17 suggest that they were in use in the 12th, possibly even into the 13th Century AD. These walls thus represent the last building phases recorded at the city of Tegea.

- The walls have the same orientation as the presumed city plan, based on the Norwegian magnetometer survey from 2003-2006. The survey and the subsequent excavations show that the main axis of the ancient city was respected in later periods and also in the final phases of Byzantine settlement at Tegea and so far confirmed by the 2010 excavation.

- A tile-covered surface that was partly excavated in 2009, and thought to represent the last paved phase of the agora, was reinterpreted as a road surface in squares C-D16.

- After having extended the area in 2010 it was clear that the paved area was not as extensive as first assumed. The corner of a larger structure made up of rough stone blocks seen in D17, runs parallel to what the team now considers to be a road.

- This building was probably abandoned in the 12th century, and it is thus thought that the road might be contemporary with and connected to the Basilica of Thyrsos. A goal of the 2011 season will be to clarify the relationship of these two parts of the city.

Early Byzantine and Late Hellenistic contexts

- Already in 2009 a solid, concrete-like floor and a rough N-S wall were uncovered in square D-E10 in the northernmost part of the excavation area. In 2010 the whole floor was uncovered, together with another wall in D11 running E-W perhaps connected to the N-S wall further east.

- The pottery found in the contexts immediately above the concrete floor as well as in the contexts connected to this structure, is dominated by small storage vessels and larger jugs and jars, and suggests a date from the early Byzantine period, more precisely between the end of the 4th to the beginning of the 5th Century AD. The concrete floor itself is very likely earlier, and perhaps even Hellenistic. It was later reused in the Byzantine period when the N-S wall was laid across the Hellenistic floor.

- To the east of the wall in square E10 a very different archaeological context appeared. An almost square area consisting of sooty soil with pieces of charcoal contained several whole vessels.The finds, including a Megarian bowl and some Roman terra sigillata, suggests that the context can be dated to the 1st Century BC. The character of the finds in this area indicate that this floor was in use in the 1st Century BC and not reused in later periods, unlike the concrete floor to the west.This is important as it shows that not all areas of the ancient city were reused after the early Roman period.

The northern trial trench

- A small trial trench, 5 x 10 meters, was opened in the far northern part of the field, in squares B-C 3-4.This trench was opened mainly to check whether the stratigraphy was similar to the main excavation area. However it turned out to be considerably different. Despite the trench having been excavated down to a depth well below the rest of the excavation area no building structures were uncovered. The stratigraphy was very complex, with large numbers of different cuts and fills. It seems that some of the fills might be the result of industrial activity, with remains of charcoal, and layers of clayey silt. One possible explanation is that this area was used as a clay pit for the production of tiles or pottery.

- The main part of the pottery found in this area is from the Roman period, including several Corinthian lamp fragments probably from the 2nd-3rd Century AD. The excavation needs to be extended in this area in order to gain a clearer idea of the use and chronology of this area in relation to the city centre.

Digital documentation

- In the 2010 season the project had a strong focus on digital documentation. The excavation also functioned as a field course, for students from Oslo and Aarhus Universities and so a GIS and practical survey element was included.

- The two last weeks of the campaign two archaeologists trained the students in practical use of a total station by surveying the previously excavated areas in the archaeological park of Palaia Episkopi.The students surveyed the altar of the Roman emperor, and the Hellenistic stoa with its drain and statue bases at the Agora.

- In addition to this, the team was allowed to survey within the building that houses the mosaic from the so-called Basilica of Thyrsos.

- After the field course, the Norwegian surveyors mapped the rest of the Byzantine structures and buildings at the agora, and startedsurveying the stones of the Hellenistic theatre one by one. So far the stones to the west of the bridge have been mapped.

- Many more stones are thus left to survey for the students attending the field course in 2011. The Temple of Athena Alea will also be digitally surveyed in 2011.

- After the 2010 season we can be reasonably certain that the last phase of human activity at the site was in the 12th-13th Century AD.For the season of 2011 it is planned to expand the excavation area further towards the southeast and thus closer to the Basilica of Thyrsos.

- By doing this, we hope to further explore the Byzantine buildings and the road in the southern part of the trench more thoroughly.

By Linn Trude Lieng, IAKH, University of Oslo(Archaeological remarks are based on Knut Ødegard’s report from the excavations of 2010

- The 2010 excavation team Fig.1: Aerial photograph of the excavation trench overlaid with the excavation’s grid system (Photo: Todd Brenningmeyer. Illustration: David Hill) Byzantine walls in D15 (Photo: Linn Trude Lieng) The excavation area towards the north (Photo: Linn Trude Lieng) The excavation area towards the south (Photo: David Hill) A lamp in situ in E10 (Photo: David Hill) Surveying the mosaic of the Basilica of Thyrsos (Photo: David Hill)

Fieldwork in Tegea 2009

By Linn Trude Lieng, Institute of Archaeology, University of Oslo.

Introduction

- This report will present the preliminary results from the first season of the scheduled 5-year excavation program at Ancient Tegea, Greece. Included here will also be a description on life outside the excavation trenches and excursions we undertook during the three weeks of the excavation. The account of the archaeological excavation and the closing remarks are based on the Norwegian Institute at Athens’ press release on the result from the excavations.

- The Hellenic-Norwegian Excavations are undertaken as cooperation between the 39th Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, the 25th Ephoria of Byzantine Antiquities and the Norwegian Institute at Athens under direction of Dr. Anna Vassiliki Karapanagiotou, Dr. Dimitris Athanassoulis and Dr. Knut Ødegård respectively.

- The background for this report is the generous research stipend I was granted from the Norwegian Institute at Athens. The stipend will be used for a month of research at the institute in Athens in connection with my Master’s thesis.

Background

- The research history of Tegea began over 130 years ago. Most of the research activity has been concentrated on the sanctuary and the first excavations took place in 1879 under direction of A. Milchhöfer where roughly 300 terracotta and bronze artefacts were uncovered. In 1882 W. Dörpfeld took over the work at Tegea doing a study of the Classical temple.At the start of the 20th century the French school at Athens obtained the rights for doing research in Tegea, and several campaigns were held from 1900 to 1902 where more of the temple’s foundations, architectonical fragments and fragments of sculptures and inscriptions and also bronzes and pottery shards were found.

- Greek archaeologists carried out an excavation in 1908, and the French school at Athens under direction of Charles Dugas carried out excavations in the years of 1910 to 1913. After this, research in Tegea came to a halt until the 1960s where the American School of Classical Studies at Athens did research on the temple proper, and 1976-77 when the Greek Archaeological Service conducted excavations at the site (Hammond 1998:8-9; Voyatzis 1990:20-21; Østby et al. 1994:89-90).

- In the 1980s Dr. Erik Østby worked on identifying the foundations inside the foundations of the Classical temple, and in 1990-94 he, on behalf of the Norwegian Institute at Athens, directed an excavation that confirmed the identification of the foundations of the Early Archaic temple inside the foundations of the larger Late Classical temple (Hammond 1998:13-14; Voyatzis 1990:22; Østby 1986; Østby et al. 1994:94-95).

- The Norwegian Institute at Athens has thus been involved in research on Tegea since its foundation in 1989, but up to the mid nineties research had mostly been restricted to the temple area.

- These investigations collected detailed information on the sanctuary. However little was known about the surrounding landscape, and no modern investigations had been made in the city of Tegea.

- To be able to understand the development of the sanctuary within a wider context there was need for more information of a regional kind, and an archaeological survey was directed by Dr. Knut Ødegård from 1998 to 2001 (Ødegård 2005:209-11). The Norwegian Arcadia Survey focused on the size and extension of the ancient city through documenting the density of archaeological material on the surface and this formed the background for a magnetometer survey of the ancient urban area in 2004 through 2006. The magnetometer survey documented important remains of the city plan and a regular street grid, a large rectangular marketplace and possible traces of the fortifications were indicated.

Left: Density of pottery fragments from the surveyed fields, showing probable extension of the city of Tegea.Right: Plan from the magnetometer survey with possible street grid and the agora indicated.

Field work

- The main aims of the first season of the scheduled 5-year excavation program at Tegea were to gather information on the stratigraphical and chronological sequence in the centre of the ancient city of Tegea and to check the results of the magnetometer survey mentioned above (Ødegård 2009).The participants in 2009 was Ole-Christian Aslaksen (Archaeologist/GIS surveyor, University of Oslo), Dr. Vincenzo Cracolici (Archaeologist, University of Palermo), Lene Os Johannessen (Archaeologist, University of Oslo), Lise-Marie Bye Johansen Archaeologist, NIKU – the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research), Dr. Harald Klempe (Geologist, Telemark College), Linn Trude Lieng (MA student in archaeology, University of Oslo), Mari Malmer (BA student in archaeology, University of Oslo), Panagiotis Riganas (BA student, University of Peloponnese), Jo-Simon Frøshaug Stokke (Archaeologist, University of Oslo).In addition to Dr. Karapanagiotou and Dr. Athanassoulis from respectively the 39th Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities and the 25th Ephoria of Byzantine Antiquities, Vasilliki Papadopoulou (the 39th Ephoria) and Peny Koliatsi (the 25th Ephoria) supervised the excavations. Lina Karavia and Nikos Govitsas from the Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of Arcadia provided the total station and worked with the Norwegian GIS surveyor.

Archaeological excavation

- The area of excavation is where it for more than 100 years has been presumed the centre of Ancient Tegea would be situated, i.e. at Palaia Episkopi, where a Middle Byzantine town was constructed on top of the remains of the Hellenistic theatre. The excavations in 2009 were conducted on property belonging to the Hellenic Ministry of Culture to the west of the ancient theatre and the urban centre and immediately north of the 5th century AD Basilica of Thyrsos. Two trial trenches of 1 by 5 meters were opened this year, and they were laid out over what was presumed to be the agora and a road crossing using the plan from the magnetometer survey as a guide. The trial trenches were dug approximately 1 meter deep using pickaxe, shovel and hoe, and the topsoil contained mixed archaeological material from the Classical to the modern period. In the southern trial trench we encountered a layer with a dense concentration of broken roof tiles. The two trenches were extended to 5 x 10 meters using a mechanical digging machine. We laidout a grid in 2 x 2 meter squares, and excavated stratigraphically.

- In the southern trench, the ‘tile fall’ we first believed belonged to a collapsed building, rather seems to be the last of a long series of pavements of a large square. The pavement most likely belongs to the ancient agora of Tegea, and is probably to be dated to the 12th century AD and thus signifies the last phase of urban life at Tegea.Trial trenches excavated through this pavement documented several similar surfaces from the Byzantine period, probably carried out to raise the ground level because of poor drainage. In the far north-western corner of this trench we exposed large amounts of slag from a metal workshop of the Byzantine period. The excavation in the northern trench showed no remains of the agora. It was expected that the agora did not stretch this far north based on the magnetometer survey conducted in 2004. Instead remains of Byzantine buildings were found. One of them, so far of uncertain date, had a concrete floor, perhaps a pressing-floor that once formed a part of an agricultural unit.

Left: Photo towards south of the two trenches. The Basilica of Tyrsos upper left in the photo (photo: Knut Ødegård).Right: The Byzantine floor in the northern trench (photo: Knut Ødegård)

Total station survey

- Parallel to the archaeological excavations a total station survey was conducted. Surveyors from the Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of Arcadia worked together with the Norwegian surveyor, and they used a Leica 400 total station to map the area.

- A coordinate system was laid out and named with Greek letters along the north-south axis and numbers along the east-west axis.This grid aided the documenting Ephoria’s process of connecting finds to the excavated areas.

- In addition to this all finds and structures were digitally surveyed, and digital maps over the excavated areas has been made using ArcGis. Fixed points for geo referencing our maps were laid out by George Orphanos with an inaccuracy of 1 cm.

Left: Surveying special finds in the northern trench (photo: Lene Os Johannessen)Right: Plan over the excavated area (illustration: Ole Christian Aslaksen)

Finds

- Finds were processed by the Ephorate. Whenever special finds like metal or coins were made, the Ephorate registered it,bagged and tagged it, and brought the finds to the museum in Tripolis for safekeeping. Pottery was bagged according tosector and context at the end of each day, and brought to the apotheke in the village of Alea by the Ephorate. The finds bagswith pottery were signed out the next day, and washing, sorting, photographing and interpreting of the pottery could take place.

Left: Washing pottery in the apotheke (photos: Lene Os Johannessen).Right: An earring found close to the Byzantine metal workshop (photo: Jo-Simon Frøshaug Stokke)

Dissemination and media contact

- During the three weeks of excavation at Tegea, we had a film crew following us. The background for this was that a movie producer was making a movie on the region of Arcadia, and an ongoing archaeological excavation was interesting to include in this documentary. The whole archaeological team were interviewed for this production that eventually will be aired on Greek national television. A journalist in a local newspaper wrote two stories on the archaeological project, and this led to some interest in the local community with people visiting the site.

Accommodation

- The Municipality of Tegea provided the accommodation for the excavation team. Since we were such a large group the students and archaeologists were placed in the Peter Orphanos medical centre of Kerasitsa, a small village not too far from the excavation site. Dr. Ødegård and the survey team from the University of Bergen which joined us after a week lived in cottages in the village of Ano Doliana, overlooking the Tegean plain.The Municipality of Tegea had made the medical centre habitable by installing showers and providing beds. In addition to this the Norwegian Institute provided necessities like kitchen equipment and linen from the Norwegian guesthouse in Athens.

- The medical centre and the village of Kerasitsa proved to be a good home for us archaeologists. We ran a well-functioning household with teams for cooking and cleaning. Everyone contributed with what they did best. The early birds bought bread before the communal breakfast, and some preferred washing up to cooking and this arrangement made everyone happy.We enjoyed some great, home cooked meals together and the good atmosphere at home made it easier to live andwork so closely together.

Left: The Peter Orphanos medical centre in Kerasitsa (photo: Lene Os Johannessen).Right: The excavation team at home (photo: Linn Trude Lieng)

Excursions and life outside the trenches

Thanks to the generosity of the Norwegian Institute at Athens, we were let to use the institute’s 8-seater car “The Lion”.The name derives from the Coat of Arms of Norway that adorns the side doors of the old Fiat. Having a car made things a lot easier for us, both getting to and from the field, shopping for groceries in Tripolis, and getting around, visiting sights in the Peloponnese during weekends.

As a recreational trip in the afternoons going to the coastal town of Astros for a swim was popular after a long, hot day in the trench. Driving around we got to see large parts of the different regions of the Peloponnese with its wild and beautiful nature. We visited many of the major sights around the Peloponnese like Argos with its Heraion, Mycenae, Sparta, Asea, Bassae and Olympia, and also the beautiful towns of Nafplion and Zaxaro. Being able to visit places like these on our time off made our stay in Tegea even more rewarding and interesting.The final dinner for the participants in the project were held in the village of Ano Doliana, and with its breathtaking view over the Tegean plain this was the perfect place to round up the 2009 field season in Tegea.

Closing remarks

- Due to the short, three-week field season of 2009 the results are limited. It should be emphasised however that we now possess certain archaeological information on the last phase of urban life at Tegea. We have also ascertained that the urban history of this site is long and complex, and that the next seasons of field work will provide insight into the development of the city from a probable foundation in the Late Archaic Period through the Classical and Hellenistic periods and into the later history of the city in the Roman and Byzantine periods.Through excavations this year we have collected finds from all these periods from the topsoil and from Byzantine contexts.Since our excavations are conducted right in the centre of the ancient city, Tegea could provide an example on how the city changed character from the Roman to the middle Byzantine period.The presence of Slavic pottery from the excavations marks one important phase of this transition (Ødegård 2009).

Acknowledgments

- We wish to thank the Greek Ministry of Culture and especially the 39th Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities and the 25th Ephoria of Byzantine Antiquities that with all their help and cooperation made this excavation possible.

- We wish also to thank the Mayor of Tegea and the Municipality of Tegea that have been most helpful with all practicalities and showed great interest in our project.Finally we wish to thank the Norwegian Institute at Athens. Director Dr. Panos Dimas and the administrative staff have arranged everything locally in Greece so this project could run as smooth as possibly, even though planned from Norway.

Linn Trude LiengOslo, the 7th of December 2009for The Norwegian Institute at Athens

Excavations at Tegea in 2009-Press release

SEE Report on the Tegea excavation

- The first season of a scheduled 5-year excavation program at ancient Tegea was carried out in june/july this year by the 39th Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, the 25th Ephoria of Byzantine Antiquities and the Norwegian Institute at Athens.

- The main aims of this first season were:1. To gather information on the stratigraphical and chronological sequence in the centre of the ancient city of Tegea and2. To check the results from the magnetometer survey conducted by the Norwegian Institute at Athens at the site 2004-2006.

- The area of excavation is where the centre of ancient Tegea has been presumed to be situated for more than 100 years, i.e. at Palaia Episkopi, where the Middle Byzantine metropolis was constructed on top of the remains of the ancient theatre.The excavations in 2009 were conducted on property of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture to the west of the ancient theatre and the metropolis and immediately north of the 5th century AD Basilica of Thyrsos.Two trenches of 5x10 meters were opened up this year.

- After initially digging through about 1 meter of topsoil with mixed archaeological material from the Classical to the modern period, we encountered in the southern trench a surface with a dense concentration of broken rooftiles.

- This does not seem to be a collapsed building, as we first thought, but rather the last of a long series of pavements of a large square, very probably the ancient agora of Tegea.This last pavement is probably to be dated to the 12th century AD and signifies the last phase of urban life at Tegea.

- Trial trenches excavated through this pavement documented several similar surfaces from the Byzantine period, probably carried out to raise the ground level because of poor drainage.In the far north-western corner of this trench we encountered copious slag from a metal workshop of the Byzantine period.

- In the northern trench, no remains of the agora was found, but based on the magnetometer survey conducted in 2004 it was expected that the agora did not stretch this far north.Instead remains of Byzantine buildings were found, one of them, so far of uncertain date, had a concrete floor, perhaps a pressing-floor that once formed a part of an agricultural unit.

- In the summer of 2009 only a short fieldseason of 3 weeks was carried out and the results are for this reason limited. It should, however, be emphasized that we now possess certain archaeological information on the last period of urban life at Tegea.

- We have also ascertained that the urban history at the site is long and complex and that the next seasons will provide interesting insight into the development of the city from a probable foundation in the Late Archaic Period through the Classical and Hellenistic periods and into the later history of the city in the Roman and Byzantine periods.We have already collected interesting finds from all these periods from the topsoil and from Byzantine contexts.

- Since our excavations are conducted right in the centre of the ancient city, Tegea could provide a very interesting example on how the city changed character from the Roman to the middle Byzantine period. The presence of Slavic pottery from the excavations marks one important phase of this transition.

Knut Ødegard

The joint project is directed by Dr. Anna Vassiliki Karapanagiotou of the 39th Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Dr. Dimitris Athanassoulis of the 25th Ephoria of Byzantine Antiquities and Dr. Knut Ødegård of the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Institute at Athens.

***

FIELDWORK AT PETROPIGI (KAVALA)

Excavation of small 13th century Byzantine statio on the ancient Via Egnatia east of Kavala

Transformed into Ottoman kervanseray in the 15th century

Director: Prof. Siri Sande (University of Oslo)

Ten seasons 1993-2002

- 1992 the Norwegian Institute was offered a small Byzantine fortress near the village of Petropigi 20 km east of Kavala as an archaeological project by Charalambos Bakirtzis, then ephor of Byzantine antiquities at Kavala. The next year the field work started, going on for the seven summers. Of these the first five consisted of excavations, a further two were dedicated to the measuring and conservation of the monument, and the final three to the study of the finds.

- The fortress takes its name after the neighbouring village of Petropigi, as its ancient name is not known. The monument is situated on the southern side of the main road between Kavala and Xanthi, 9.23 m. above sea level, on a plain stretching down to the sea. North of the road the terrain starts to rise towards the Rhodope mountains, which form a splendid backdrop when one sees the fortress from the south. Originally the shoreline must have been closer to the fortress than it is today, and the distance to the Petropigi village was longer as the old village was located higher up on the mountain slope. With the draining of the marshlands near the coast new land for cultivation became available, and a new village was constructed closer to the main road. Only traces of the old Petropigi can be seen today.

- The fortress is oriented north/east-south/west, and it lies exactly parallel to the modern road. Because of this parallelism it is probable that the modern road at this point follows the course of the ancient Via Egnatia. The remains of the latter may either be buried under the tarmac, or possibly further south, where a dirt road now runs. Unfortunately it has not been possible to lay out a trench northwards to try to locate the road, as only the plot immediately adjacent to the fortress belongs to the Greek state. The surrounding fields are privately owned.

- Though the Petropigi fortress lies in the midst of cultivated fields, no trace of human occupation such as pottery shards has been found in the neighbourhood. There appears to have been no settlement in the immediate vicinity. Already before the excavation started, Bakirtzis suggested that the fortress was a statio, that is, a fortified staging post. Our investigations so far have corroborated this hypothesis.

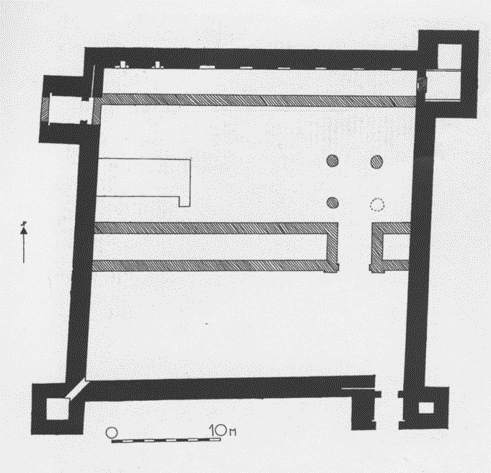

- The inner measurements of the fortress, 29,6x29,3 m, correspond to 100x100 Roman feet. Its walls are constructed of mortar, stones and bricks, a technique used from the early Byzantine period onwards. One band of bricks runs continuously through all four walls at the same height, while the rest of the bricks are distributed more unevenly for shorter stretches. There are some slight differences in the size of the bricks, which may be attributed to different building stages.

- The building technique is in itself not sufficient to allow a precise dating, since it was used over a long period. As usual, the walls of the fortress were constructed around a wooden scaffolding. When the work was finished, the beams were cut and the scaffolding removed, leaving the timbers in the walls to decay there. During our excavation we found a tiny piece from the scaffolding in the mortar in the south/western tower. It was subjected to a C 14 analysis at Uppsala, Sweden, which suggested a date between A.D. 1275 and 1350. For historical reasons it seems most reasonable to opt for a construction date in the 13th century, when there was a certain building activity following the recapture of Constantinople from its Latin occupants.

- The layout of the fortress was changed in the course of time. Originally it had two gates, one in the south/east and one in the north/west, and two towers, one in the south/west and one in the north/east. The projecting walls of the gates were probably vaulted. At a later stage these walls were extended and fitted with a portcullis, the slots of which are still visible. Contemporarily a tower was added to the south/eastern corner. The north/western tower was enlarged, and a room inside added on an upper level. There is a “seam” in the wall of the south/western tower suggesting that this, too, may have been strengthened.

- It is likely that these alterations were made not long after the construction of the fortress, during the turbulent 14th century, a period characterized by Byzantine civil wars and the incursions of various powers such as the Serbs, the Catalan Company and finally the Ottoman Turks, whose conquest of Thrace and eastern Macedonia started in the 1360’s. If the Byzantines themselves strengthened the fortress, they probably did it during the first half of the 14th century, while they still exercised some control, but it is, of course, also possible that the decision to fortify it was made by one of the temporary masters of that particular stretch of the road during the second half of the century. The fortress could not have withstood an army with siege equipment, but it could probably repel attacks from brigands, of whom there were many in the 14th century. The fortress is, in fact, very conservative in its typology, and differs little from its early Byzantine prototypes.

- Inside the fortress several structures came to light. In the southern area the somewhat flimsy substructures of two buildings remain. Between them there is a channel which runs through the outer wall of the fortress. The buildings give the impression of being utilitarian structures such as stables or the like. The substructures are not datable, but they are probably as old as the outer walls of the fortress, since they take the channel into account.

- The structures in the middle and the northern area of the fortress are better preserved and more characteristic. The most important one is a long building which practically divides the courtyard in two. It is oriented according to the points of the compass contrary to the fortress walls, which, as remarked above, deviate slightly in accordance with the course of the Via Egnatia. The differences in orientation are only perceptible when measured. The building is divided into one longer and one shorter unit with an aperture between them, which gives access to the northern part of the courtyard. The shorter unit is in line with the south/eastern gate. Apart from having a slightly different orientation from the fortress itself, the two units are constructed in a different technique, the so-called cloisonné, where the stones are framed by horizontal and vertical bricks. The floor of the long building was stuccoed. No door was found, neither in the longer nor in the shorter unit. This suggests that the lower part of the building was used as a basement, and that there was a second story with access from outer staircases which probably led to a walkway or gallery, all in wood.

- The cloisonné technique was also used in a structure running along the inside of the northern fortress wall in its full length. Since it was demolished more thoroughly that the building in the middle of the courtyard, very little of it remains. Though it stretches from one end of the fortress to the other, there is no trace of a bond higher up on the walls. This may mean that the structure was no building, but simply a low platform.

- The northern fortress wall is marked by eight recesses at about equal distance from each other. The one in the west, which is better preserved than the rest, shows that the recesses were fireplaces with chimneys. They seem to be secondary in relation to the fortress wall, and were probably inserted into it when the platform along it was built.

- The platform bordered on the north/eastern tower and the north/western gate, both of which were closed. The gate was closed twice, both towards the courtyard and outwards. The outer wall is in cloisonné technique, indicating that the builders that constructed the platform and the long building in the middle of the courtyard were also responsible for the closing of the tower and the gate.

- The cloisonné technique finds its closest parallels among early Ottoman buildings in Western Thrace, such as the han in Traianoupolis and the imaret in Komotini. A C 14 dating of charcoal found inside the long building in the courtyard, also gave a date in accordance with the Ottoman occupation of Thrace and Macedonia, since it suggested the period A.D. 1410-1425. The Ottoman invaders obviously turned the Byzantine statio into a Turkish kervansaray. Since these constructions have the same function, they needed only to make few changes. The closing of one of the gates was one of these, as Turkish kervansarays have normally only one gate, not two. It may seem odd that the gate nearest to the Via Egnatia was closed, but the new masters probably preferred to have the gate in the same area as the utilitarian buildings, and the sleeping quarters out of sight.

- A platform with fireplaces in the back wall is a typical feature of many Ottoman kervansarays, and can be seen illustrated in miniatures, for instance. The travellers slept wrapped in their cloaks or blankets with their mounts or tethered to the platform or immediately in front of it. The fireplaces in the wall behind them gave them warmth, and also possibilities to cook their food. There were few, if any facilities in these kervansarays, which are mostly described as being completely empty. A French traveller who visited the Ottoman Empire in the 17th century and undertook a journey with a caravan, was advised by an Armenian friend in Constantinople to bring with him everything he might need, even down to the shoes of his horse.

- There was, however, the possibility of having one’s horse shod. The blacksmith was an important feature in Byzantine stationes and Turkish kervansarays. We did, in fact, find his forge in the Petropigi fortress. It was located close to the westernmost chimney in the northern wall.

- Since the travellers brought with them pots and pans and cutlery and departed with it again, few objects came to light inside the fortress. This is a marked difference from settlements. What we found, was mostly pottery which had been accidentally broken by the travellers. Most of it was cheap “kitchen ware” such as people are not afraid to lose, though a few sherds of late Byzantine glazed pottery turned up. The coins we discovered during the excavation, were all Ottoman, the majority cheap and badly preserved copper coins. One silver coin from the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent could be dated to the middle of the 16th century A.D. The earliest coins seem to be datable to the beginning of the 15th century A.D., while the latest coins bore a characteristic star pattern which is found on some of the coins of Sultan Murat the third (A.D. 1574-1595). Judging from the finds, the fortress of Petropigi would seem to have been used as a kervansaray at least during the 15th and 16th centuries.

- When it was rebuilt, great care was lavished on it. Apart from the structures in cloisonné technique, we excavated a stucco floor in the north/western area of the courtyard. Every stone in this building had been removed, so it is impossible to date it by technical means, but as it would not have been built before the north/western gate was closed, it must been Ottoman in date. We have not yet determined its function. In the north/eastern part of the courtyard the lower parts of two thick stucco pillars (diam. 1 m.) and the imprint of a third one came to light. They were probably four in number originally, and must have carried an elevated structure, possibly a small mescid, a prayer room.

- At some point after the 16th century, all the Ottoman structures were dismantled. This clearly happened by public decree and under public control, since the work was very thorough. The walls were all at once taken down to the same level, presumably to get hold of the bricks, which could be reused in other public buildings. We found much larger quantities of stones than of bricks, which suggests that the latter were carted off. With regard to the outer walls of the fortress, the picture is quite different. They were left to decay and were gradually taken down by the local farmers, when the latter needed building materials. They, incidentally, wanted stones, not bricks.

- Because they were left to themselves, the fortress walls are preserved to different heights. The southern and western walls have always been visible to a considerable height, whereas the northern wall is especially badly preserved. This is due to the presence of fireplaces. Long after the fortress had ceased to function as a staging post, it was used by the local farmers and herdsmen, which almost up to the present day used to lighten fires in the old fireplaces. The rapid changes in temperature weakened the wall and caused it to crumble gradually, a process which probably lasted for centuries.

- As suggested by the coins, the Petropigi fortress was used for its original function at least till the end of the 16th century. We do not know when the dismantling of its inner structures took place, but the reason was probably that a better staging post had been found. The distance from Kavala is only 20 km, rather short by Ottoman standards (30 to 40 km seem to have been normal, depending on the road). By moving 5 km further east, one arrives at Khryssoupolis, an old town which is known to have been a statio already in the Byzantine period. It is therefore likely that, at a certain point, the Petropigi fortress was abandoned as an official staging post in favour of Khryssoupolis.

- In the centuries following the Ottoman conquest, life was difficult in Thrace and Eastern Macedonia. Large segments of the original population were transferred to other parts of the Ottoman Empire, and towns and villages were depopulated and in a sorry state. The decline probably started already in the late Byzantine period, otherwise the Petropigi fortress would not have been built. Its construction suggests that Xryssoupolis was not safe enough as a statio, a state of affairs which continued well into the Ottoman period. In the 17th century the conditions of the Christian population ameliorated somewhat, and repopulation of sparsely populated areas was encouraged. With towns and villages more populous and with increased peace and prosperity, it would have been easier for travellers to find accommodation in inhabited areas, and the isolated kervansarays began to go out of use.

- Having ceased to function as a staging post, the Petropigi fortress continued to be used by the local population. In the south/western tower we found a fragment of an 19th century Turkish pipe together with several bones from sheep and goats, evidence that it was used as a lair, probably by herdsmen. There were also a number of 18th-19th century pottery sherds in the upper layers in the courtyard of the fortress. There we also found small, rectangular flints. In all likelihood they belonged to a sort of sledge used for threshing, called tykane in Greek. It was employed in Greece and Anatolia till well into the 20th century, and specimens can still be studied in various local museums. It is easy to see that when the ruins inside it had become covered with earth, the courtyard of the Petropigi fortress would have been ideal for threshing. We also found several horse-shoes. Some of these are recent and should be connected with the various agricultural activities that have been going on in the fortress until the 20th century, while the oldest ones were possibly lost by travellers in the period when the fortress still retained its original function.

- The Petropigi statio or kervansaray is a good example of acculturation, showing, among other things, how the Ottoman invaders simply took over the Byzantine infrastructures and adapted them to their own use. Neither the Ottoman nor the Byzantine name of the staging post is known, but Charalambos Bakirtzis suggested that it is mentioned in historical sources as a place where members of the Catalan Company came together in 1307 in connection with the disbanding of the Company. Perhaps studies of old maps and documents may yield more information with regard to identity of the fortress.

Text by Siri Sande

***

NORWEGIAN ARCADIA SURVEY (NAS) - 1998-2001

Coming soon

***

INVESTIGATIONS IN THE TEMPLE AND SANCTUARY OF ATHENA ALEA (1991-1994, 2004)

Publications:

Coming soon